When Charlotte Webb asked me to write a piece about the future of work for Furtherfield, I immediately thought about Utopoly. Even though this game doesn’t directly discuss how we will be employed or occupied in the future, it creates a rare space where people can re-imagine a different society in which values, forms of exchange and social relations are reconsidered and reconfigured.

To better understand the ethos behind Utopoly, I interviewed Neil Farnan, who is currently undertaking a PhD at University of the Arts London with the research title ‘Art, Utopia and Economics’. He became an Utopoly advocate, introducing many ideas and concepts featured in its current iteration. Neil’s interest in designing a utopian version of Monopoly was initially shaped by his previous studies in User Interface Design, where he developed an interest in Scandinavian design practice and Future Workshops.

Francesca Baglietto: What is Utopoly? More specifically, how does it relate to and differ from Elizabeth Magie’s original version of Monopoly?

Neil Farnan: Utopoly is both a tool for utopian practice and a fun game. It draws on Robert Jungk’s Future Workshop methodology to re-engage people’s imagination and ideas for a better society and incorporates the results into a ‘hack’ of Monopoly.

Elizabeth Magie’s original game (1904) was intended to show how landlords accumulate wealth and impoverish society. Players could choose either a winner takes all scenario or one where wealth was distributed evenly via a land tax. Magie also hoped that children’s sense of fairness meant they would choose the latter and apply these ideas in adulthood. But the Monopoly we have today normalises and celebrates competitive land grabbing and rentier behaviour and Magie was airbrushed out of history and replaced with a more acceptable mythology of the American Dream.

Whilst Magie’s game informed players about the current situation, Utopoly gives people the opportunity to imagine and incorporate values and attributes they would want in a more utopian world. Players are able to determine the properties, the chance and community cards and even rules of the game. The rules being determined by the players means the game is a work-in-progress, however some features that work well can get adopted and carried through to the next iteration.

FB: As you just said, Utopoly doesn’t have a definitive form and rules but changes with each interaction. So, while the future of Utopoly is still in progress, what I would like to know is who started the project and how has this evolved so far?

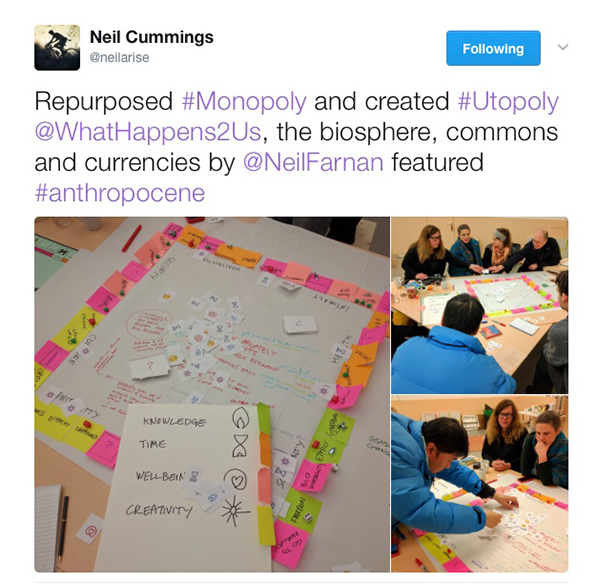

NF: Critical Practice, a research cluster at Chelsea College of Arts, played a central role. We were concurrently developing both Utopoly and an event #TransActing – A Market of Values, and the current version of Utopoly is a synergy of aspects of these two projects. The first ‘hack’ of Monopoly occurred at Utopographies, co-organised by Critical Practice (28th – 29th March 2014), where the elements of the game were redesigned to incorporate utopian values. Inspired, we decided to continue developing the ideas and a second ‘hack’ took place (December 2014). Some of the ideas and values that emerged from this iteration fed into and were represented in the design of the currencies used for #TransActing. A further opportunity presented itself for another ‘hack’ within the research event ‘What Happens to Us’ at Wimbledon College of Art. This iteration was hosted by Neil Cummings and I was invited to include the currencies developed for #TransActing. It was here that Utopoly as a ‘method’ began to emerge, a method for collectively producing possible futures. I have since convened a number of iterations using a large laminated board to facilitate design adaptations and ease of play.

Additionally, researchers from the international ValueModels project (modelling evaluative communities utilising blockchain technology) recently visited Chelsea – we played Utopoly and they loved the method. They have since been inspired to use Utopoly in their research, and I’m excited to receive their feedback on how their version develops.

FB: Utopoly is experimenting with possible new monetary ecosystems in which multiple currencies and values might be exchanged. How might these currencies work and what are they inspired by?

NF: The currencies developed for #TransActing generated the concept of an ecosystem of value exchange and these are used in Utopoly. I have since come across the work of economist Bernard Lietaer, who highlights the problems of mono-currency economies and advocates for a monetary ecosystem using multiple currencies. With their origins in subjugation and taxation, mono-currencies are tools for value extraction. They also contribute to cycles of boom and bust, resulting in the withdrawal of money from the economy and the prevention of economic activity. Historical evidence suggests that economies operating multiple currencies are more resilient – they work in a counter cyclical manner compensating for this withdrawal and allow the economy to keep working.

The irony of Monopoly is that the winner is ultimately left in control of a non-functioning economy. A more preferable state would be to have a healthy flow of values in balance where people are able to exchange their contributions in a mutually beneficial way. A feature of Utopoly is that players no longer seek to own all the property but work together for the common good. The currencies are used to bring privately held properties back into the commons. The economist Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel prize for debunking the myth of the “tragedy of the commons” (Ostrom, 2015) demonstrating the benefits and effective use of common resources. Utopoly also allows economies of gifting and sharing.

I am currently working on ways of modelling innovations such as the blockchain and associated digital currencies.

FB: How would you interpret “work” in this utopian economy? For example, do you think the relation between paid work and unpaid work and/or people’s dependence on employment might be shaped in an ecosystem in which assets/values are brought into the commons to generate value/wealth for all?

Whilst not directly about work, Utopoly reflects the future nature of wealth and values in a Utopian economy. It touches on the current abstract separation of paid work from non-paid work and people’s employment dependency.

In Magie’s original game the players collect wages as they pass ‘Go’. They then buy properties and accumulate wealth extracted from other players. On one corner of Magie’s game is the Georgist statement “Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages”, reminding us that land ownership should not provide unearned income.

As an economy develops people become less self-sufficient and more dependent on employment to meet their needs and a mono-currency makes the separation of paid and unpaid work even starker. The social contract that existed from 1950-70s where employers had a responsibility to their employees is disappearing. Outsourcing, short term and zero-hours contracts make the future of paid work increasingly precarious, and we also face further threats from automation and artificial intelligence.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato (2011) documents the substantial contribution of public investment to the success of today’s businesses. These businesses stand not so much ‘on the shoulders of giants’ but on the shoulders of a multitude of diverse contributions from society at large. A new social contract is needed to take this into account.

Fintech companies make much of the term ‘disintermediation’, but we also need a new form of ‘intermediation’ where contributions are reconnected and recognised. An ecosystem of currencies which register currently unpaid valuable activities together with a basic income could meet this need. This approach is suggested in Utopoly where people collaborate to contribute values and are valued for their contributions. The properties are brought into the commons to generate value and wealth for all.

FB: Playing seems to provide a very rare space in which, by operating in an interstice between reality and fantasy (what the psychoanalyst Winnicott called a transitional space), it is still possible for the players to imagine alternatives to our current economic system. Would you agree that the main political purpose of Utopoly is to provide such a space in order to reopen the capacity to be imaginative about economic and societal organisations?

NF: This is the utopian aspect of Utopoly, using people’s imagination as a means of prefiguring the future. We endure in a society where the mainstream orthodoxy would like us to accept that ‘there is no alternative’. One of the last great taboos is money and the associated economic system. If you consider our mono-currency as a societal tool imposed from the top down, it shapes and informs how we behave and the values we are expected to live by. In a way, it is like DNA; if we can change the DNA of our economy we could create new exchanges, values and social relations. We have become so used to this abstract construct that it is the water we swim in and the box we need to think out of. In order for people to start thinking that another world is possible we need to open up a space for imagination to play out. Art, games and play are some of the few remaining arenas available to engage in speculation about the future. Utopoly fulfils many research functions including acting as a tool for inquiry and reflexion, and a means of modelling future possibilities. It is rare for people to have the opportunity to criticise the existing state of society and work out how to reshape it. By allowing people the space to consider different approaches we can start to encourage better societal norms of exchange and interaction and construct new social contracts.