We are building CultureStake, the world’s first collective cultural decision making app (using Quadratic Voting on the blockchain) because we want to enable all communities to choose the creative experiences they want to have in their own areas. The original idea was driven by an awareness that top down arts programming is increasingly problematic. We wanted to find a way to give more people more of a say in what art and culture gets produced in their neighbourhoods – and more opportunity to be the co-creators. In a nutshell, our mission is to put the public at the heart of public arts.

Communities

We want communities to explore and learn together what we all want to experience in our localities. For example how might a theatre audience cast a play differently or a park community curate a public art exhibition?

Cultural Organisations

We want deeper, richer and more open consultation with the communities cultural organisations work for. For example, how might a city council find out which new artwork should occupy a recently vacated public plinth. Or how might an arts organisation discover which artist on their shortlist should be next summer’s blockbuster?

For Everyone

We want a data commons that widens the conversation about how art is valued by different communities around the world. For example, how might our ideas about culture change if we can see what’s important to other people?

We are using Quadratic Voting because it takes us all from confusing numbers to nuanced feelings.

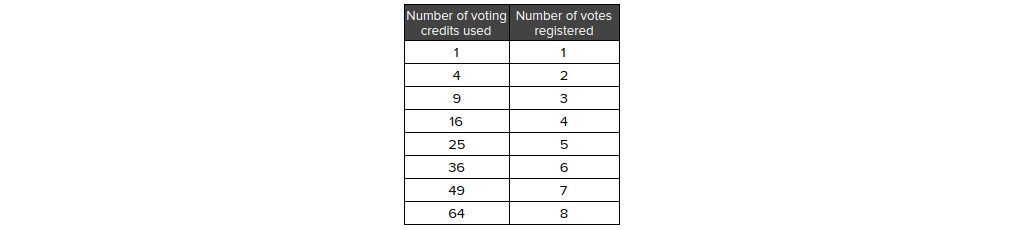

In QV voters receive a number of ‘vibe credits’ which they can allocate to different creative proposals to express their support. The quadratic function means that showing a strong preference comes at a credit cost. Or rather:

This means that QV is quite unlike any other voting process. Indeed, unlike a one person one vote system, in QV votes express not just what we care about but how much we care! This matters because one person one vote systems usually don’t present the reason why someone voted the way they did or how strongly they felt about it. Politics have taught us not to trust the way votes are interpreted. Voters’ intentions are often misrepresented and communities are polarised about the limited information. Whereas QV allows us to express the intensity of our convictions, giving each of us:

Plus we’ve designed CultureStake so vote organisers can weight the votes of those closest to the issues that matter. For example, in our use of CultureStake for the People’s Park Plinth, any votes cast inside Finsbury Park mean more overall. So those most affected get more of a say.

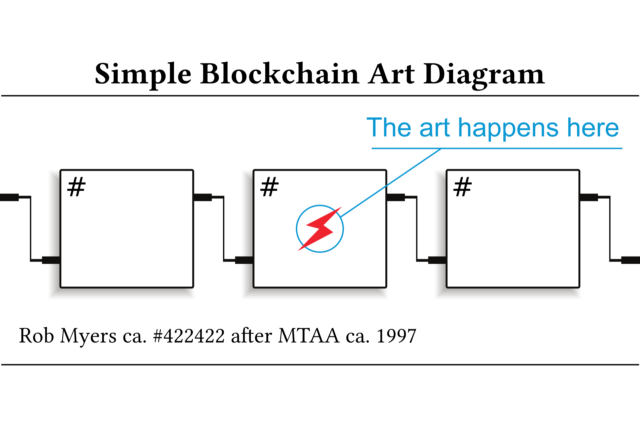

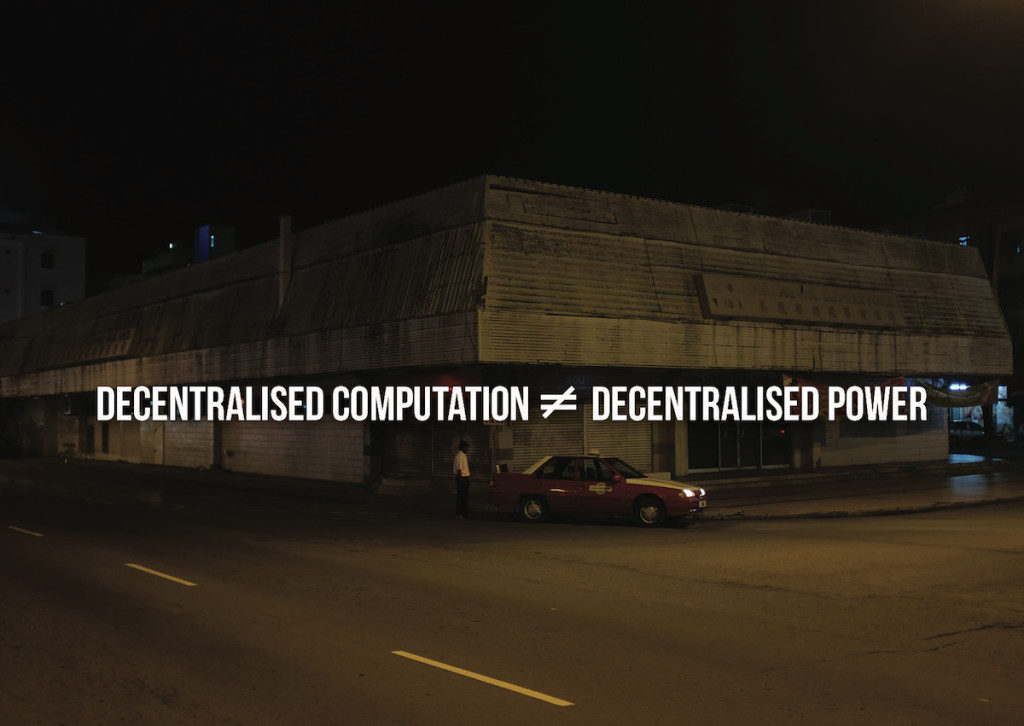

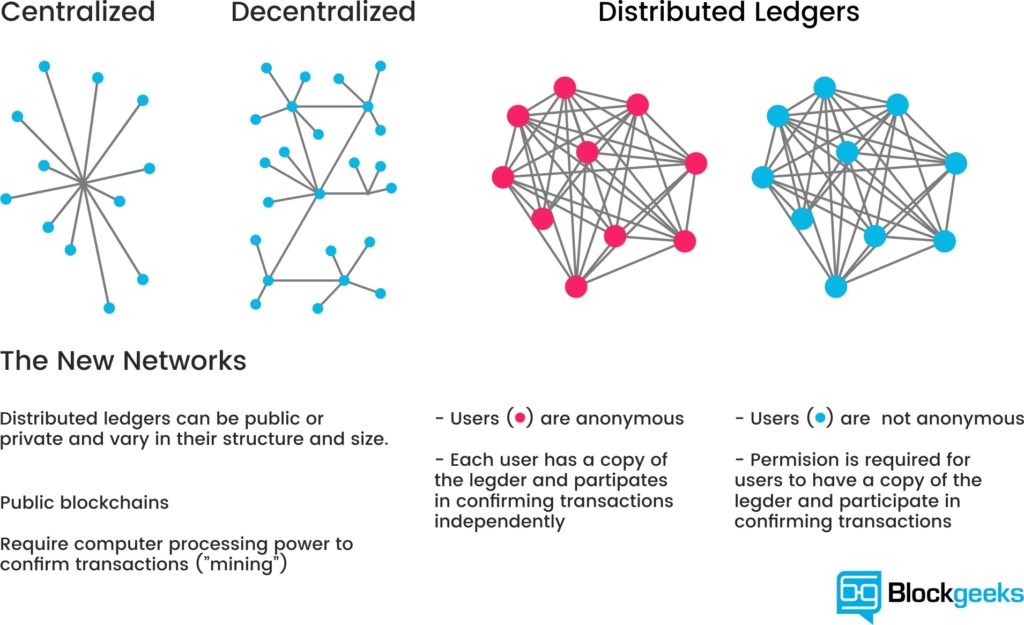

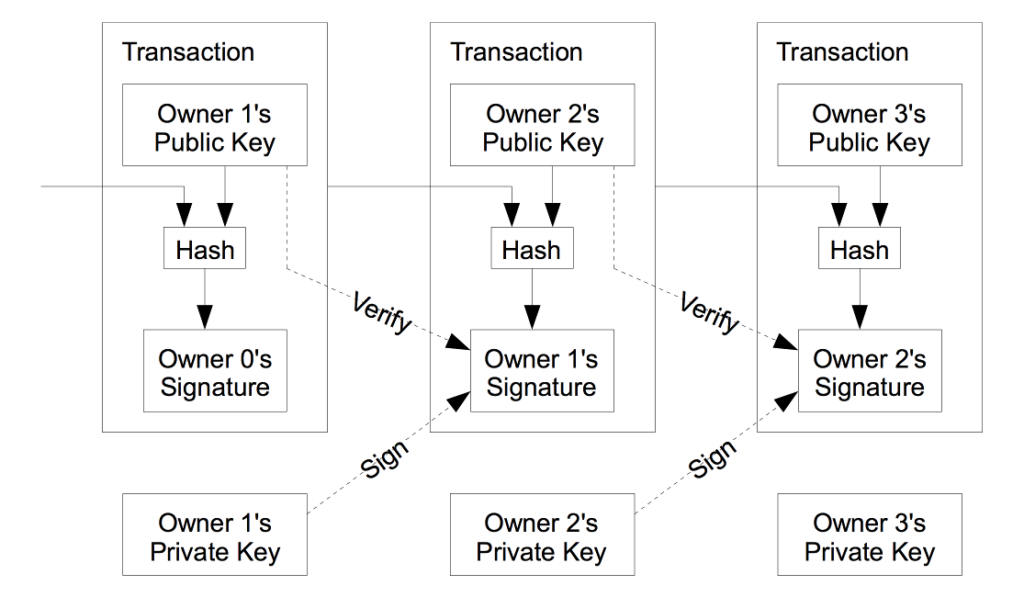

And we run all CultureStake votes on the blockchain because the blockchain is like a big indelible ledger. This means that a vote cannot be rigged and is always stored extra safely so what we can promise voters is that they can trust our system.

There are many ways to run a CultureStake vote. A theatre could develop an unfinished performance and ask communities to choose the next steps. An arts organisation might offer up a range of different events and invite communities to choose what they want to encounter. Either way, the voting system doesn’t rely on asking everyone to just pick their favourite, but rather explore their thoughts and feelings in relation to a set of questions. So the result is always knowing more about what communities think and feel. Plus, we never show what ranked 1st, 2nd, or 3rd, but rather what was selected and what thoughts and opinions drove people’s selections.

At Furtherfield we are using CultureStake to power our People’s Park Plinth initiative in Finsbury Park. The concept behind the People’s Park Plinth is that our Finsbury Park buildings and even the park itself will act as a plinth for public digital artworks chosen by our communities using our CultureStake app.

The Gallery building will therefore provide an interface where people can scan hoardings to access works which offer a range of XR-enabled experiences in the park. Annually there will be a set of ‘proposal’ artworks, which will give people a first glimpse at what can be created more fully later in the year. Everyone will have time to explore these proposals and then use CutlureStake to choose what they want.

In our pilot year we tripled local engagement and received amazing local feedback like this:

“I live nearby and I’ve been talking about this with my friends for months, it’s such a great idea, to give people a say!”

“[…]decentralisation allows people to have slower but more grassroots-based management of any decision making.”

“I think it’s good that we have a say as well. And I really love voting.”

“Usually I guess I choose art by going to a place and supporting it like that but I’ve never been involved so much in really deciding on what I will see next. And yeah it makes me actually feel good too.”

“[…] quite a lot of times actually […] art is reserved only for the higher echelons of society and I feel like this is really nice that anyone can come in and you vote for who you like or what art you like.”

“I do feel represented…”

We are now in the next phase of development and are actively looking for partners from different types of venues and communities to partner with us so we can explore their unique needs and ensure we have a robust system.

If you are a small, medium, large, networked, physical, touring, online or any other type of cultural entity that wants to deepen your community connections we would love to hear from you. We want to know how you would use CultureStake in your own context and what you would like to achieve. To find out more contact Charlotte and she’ll arrange a meet up.

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) offer unique tools for translocal peers to encode rules, relations and values into their joint ventures using blockchain technologies.

In recent years DAOs have been heralded as a powerful stimulus for reshaping how value systems for interdependence and cooperation manifest themselves in arts organising. Radical Friends. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Arts consolidates five years of research into a toolkit for fierce thinking, as well as for new forms of radical care and connectivity that move beyond the established systems of centralised control in the art industry and wider financial networks.

At a time when so many are focused on NFTs, Radical Friends refocuses attention on DAOs as potentially the most radical blockchain-based technology for the arts in the long-term. Contributors engage both past and emergent methodologies for building resilient and mutable systems for mutual aid. Collectively, the book aims to evoke and conjure new imaginative communities, and to share the practices and blueprints that can help produce them.

Radical Friends includes contributions of essays, interviews, exercises, and prototypes from leading thinkers, artists and technologists across this emerging field. This book, follows Furtherfield and Torque Editions ground-breaking book Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain.

Editors

Ruth Catlow & Penny Rafferty

Contributors

Ramon Amaro, Calum Bowden, Jaya Klara Brekke, Mitchell F. Chan, Cade Diehm, eeefff, Carina Erdmann, Primavera De Filippi, Charlotte Frost, Max Hampshire, Lucile Olympe Haute, Sara Heitlinger, Lara Houston, Cadence Kinsey, Nick Koppenhagen, Kei Kreutler, Laura Lotti, Jonas Lund, Massimiliano Mollona, MetaObjects, Rhea Myers, Omsk Social Club, Bhavisha Panchia, Legacy Russell, Tina Rivers Ryan, Nathan Schneider, Sam Skinner, Sam Spike, Hito Steyerl, Alex S. Taylor, Cassie Thornton, Suzanne Treister, Stacco Troncoso, Ann Marie Utratel, Samson Young

Publishers

Torque Editions

Design

Mark Simmonds

Cover and Inside Illustrations

Marijn Degenaar

“Radical Friends is an urgent book for the 21st Century and beyond. It shows us, in the spirit of the legendary poet and artist Etel Adnan, that the technology of the future needs to be about “togetherness, not separation. Love, not suspicion. A common future, not isolation.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist“How things are run is often more important than what is done. It may not be easy to establish alternative formats and infrastructures, but it’s certainly necessary… This collection shows that it is possible too.”

Sadie Plant“This book is about friendship, despair and hope — a beautiful, must-read for all people who are asking unanswerable questions about life, love and the end of the world.”

Franco “Bifo” Beradi“Web 3 diagonalises the principles of Web 1 and Web 2. Binaries are dead. Everything is both good and evil, emancipatory and oppressive, singular and infinitely replicable. Radical Friends navigates this confusing new terrain in a nuanced and accessible way that is liable to make you feel excited about the future of art, politics, and maybe even the world again.”

Amy Ireland“An instant seminal compendium for people who want to gain a deeper understanding of the radical potential of crypto tech for aesthetic institutions.”

Harm van den Dorpel

Join the discussion on Discord and share your questions with the speakers.

The Radical Friends Symposium discusses the value of and presents pathways to peer-produced decentralised digital infrastructures for art, culture and society – in particular through Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) for the cultural sector. The symposium takes as its inspiration the defining principles of friendship – sustained intimacy, fellowship and camaraderie – which, when applied to complex difficulties (particularly those that might otherwise be invisible to us), offers excellent design patterns for social infrastructure. To end gatekeeping and elitism in the artworld we therefore bring this spirit of deep and radical friendship as a way to build resilient and mutable systems for scale-free interdependence and mutual aid.

DAOs provide new digital governance infrastructures that allow people to pool resources, exchange economic value, and form joint-ventures, that defy national borders. DAOs enable people to agree on how risks and rewards should be distributed and to reap the benefits (or otherwise) of a shared activity now and in the future.

At a time when the mainstream artworld is focused on the personal wealth that can be amassed through NFTs, artworld DAOs offer the potential to diversify collaboration and to lower the cost of translocal self-organising, leading to new visions, vehicles and configurations for communally grounded projects. The open source artworld DAOs we do (and don’t) build now will have direct consequences for who owns the future and decides what this means for others.

So gather up your radical friends and grab your tickets for an expansive 8-hour program that includes: lectures; panel discussions; concerts; as well as hybrid talk and body-work formats. Throughout the event, participants are invited to analyse, discuss, and map the obstacles, opportunities, and implications of progressive, decentralised organisations and automation in the artworld. Plus, watch out for 4 prototype DAOs that will be unveiled during proceedings and take part in collectively awarding a 10,000 EURO development grant funded by the Goethe-Institut to 1 of them.

The Radical Friends Symposium is curated by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Penny Rafferty in dialogue with Sarah Johanna Theurer and Julia Pfeiffer (Haus Der Kunst, Munich). Participants include James Whipple (aka / M.E.S.H.), OMSK Social Club, Jaya Klara Brekke, Harm Van Den Dorpel, Cem Dagdelen, Aude Launay, Sarah Friend, Laura Lotti and Calum Bowden (Black Swan), Bhavisha Panchia and Carly Whitaker (Covalence Studios), Nicolay Spesivtsev and Dzina Zhuk (eeefff) and Massimiliano Mollona alongside Samson Young (Ensembl).

Radical Friends presents results from the DAOWO (Decentralised Autonomous Organisations with Others) project, co-founded by the Goethe-Institut London and Furtherfield with the support of Serpentine Galleries. The award-winning DAOWO is a transnational collaborative network that has been bringing together leading international institutions and communities from the arts and technology for three years to question the advantages and disadvantages of blockchain technologies for art, culture and society from a local perspective. The summit is part of the Goethe-Institut project “Lockdown Lessons”. It searches for answers on what can be learned from the Covid-19 crisis on a global scale concerning social, technological, postcolonial and civil society concerns.

Discover a new set of experimental projects to reinvent the future of arts with blockchain.

The Goethe-Institut London, Furtherfield and the Serpentine Galleries present The DAOWO Sessions, a new series of online events running from 28th January to 4th March 2021. The series explores the possibilities for the future of the artworld with blockchain by investigating what can be learned from DAOs (Decentralised Autonomous Organisations) working with Others (-WO). Each session is an eye-opening presentation and conversation around active experimentation that aims to hack, deconstruct and reinvent the arts in the emerging crypto space in response to people and their local contexts. This is a unique opportunity for cultural practitioners, representatives of arts, technology organisations, communities and anyone interested in the potential of blockchain to come together and question the future of art and society.

Curated by Ruth Catlow (artistic director Furtherfield), Penny Rafferty (writer and researcher) and Ben Vickers (CTO Serpentine Galleries) with the Goethe-Institut London, each event introduces one of five new progressive blockchain art prototypes created by DAO teams in Berlin, Hong Kong, Johannesburg and Minsk. Through live video conference, the teams will introduce their prototypes and address key questions about the potential of blockchain systems to decentralise power structures and to rewire the arts. The final session brings together the DAOWO curators in conversation with art critic Francesca Gavin.

The DAOWO Sessions are part of the award-winning blockchain programme for reinventing the arts, the DAOWO initiative, a partnership between the Goethe-Institut London, Furtherfield/DECAL and Serpentine Galleries.

All events take place at 9.00am GMT and are free to access with booking required.

(Video Broadcast in English, BSL interpretation)

For full event information and tickets please visit: goethe.de/daowo

Events and Dates:

28 Jan 2021 | BLACK SWAN DAO (Berlin)

The first event connects with Berlin to introduce BLACK SWAN DAO (Trust), an experimental initiative which responds to the increasing precarisation of cultural labour by providing cultural practitioners with tools to collaboratively organise and share resources.

4 Feb 2021 | COVALENCE STUDIO (Johannesburg)

This event connects with Johannesburg’s DAO (Covalence Studio) to introduce a network of resources, skills and support for artists and creative practitioners with the goal to rethink equitable artistic practices that can thrive under restricted movements and collapsing economic infrastructures.

11 Feb 2021 | DAO AS CHIMERA (Minsk)

Speculating on future histories of blockchains, Minsk-based initiative DAO AS CHIMERA is a unique network and a live action role play. The project aims to provide a view on the cultural, tech and start-up sphere in Belarus and to unpack emancipatory potentialities of collectivities freed from the constraints of project-orientation.

25 Feb 2021 | ENSEMBL (Hong Kong)

An Ethereum-based platform for decentralised organising of artistic production. The project explores how can DAOs learn from improvised music about value and temporally dynamic collaborations? What’s the “Score”?

4 Mar 2021 | The Machine to Eat the Artworld (online)

A conversation with the curators of the Artworld DAO think tank and the DAOWO programme, Ruth Catlow and Penny Rafferty interviewed by curator and writer Francesca Gavin. Catlow brings 25 years of experience as a curator, artist, and researcher exploring the intersection of arts and technology, emerging practices in art, decentralised technologies and the blockchain, alongside Berlin-based writer and visual theorist.

For full event information and tickets please visit: goethe.de/daowo

Please DONATE to CultureStake by participating in the Gitcoin CLR matching experiment for funding public goods.

Your donation goes a LONG way!

Using quadratic voting on the blockchain, CultureStake’s playful front-end interface allows everyone to vote on the types of cultural activity they would like to see in their locality.

CultureStake democratises arts commissioning by providing communities and artists with a way to make cultural decisions together. It does this by giving communities a bigger say in the activities provided in their area, and by connecting artists and cultural organisations to better information about what is meaningful in different localities.

Using the CultureStake app, people are invited to consider the social and cultural relevance of particular artworks to their localities. And they are given a way to rank how strongly they feel about artworks and the issues they raise. Votes are tracked and made visible, giving evidence of the types of projects communities would most value.

Currently, major artists and cultural sponsors have the upper hand and this can result in one-size-fits-all ‘blockbuster’ programming. CultureStake is a practical response to a growing demand for greater transparency about how, and in whose interest, decisions about the public good are made. It opens the field for experimentation, for robust and sustainable alternatives to centralised and private decision-making practices.

The ultimate vision for CultureStake is that governance and funding of culture are put into the hands of audiences, artists and venues, acting together in and across localities and time.

In this way, we hope to increase a shared sense of agency, imagination, and alliances.

The CultureStake pilot is commissioned by the Leeds International Festival 2020 as part of Furtherfield’s Future Fairness. This is a family-friendly fair of art and technology activities to examine the future of the world we live in, and to invite participants to choose what they want to see in Leeds in the future.

Using the CultureStake voting app they will decide together which project they would like to see commissioned on a larger scale in Leeds.

Quadratic voting (QV) was developed as an improvement on one-person-one-vote collective decision-making processes. It attempts to address the associated “tyranny of the majority” problems and data loss about voter intentions (so well understood by Post Brexit citizens of the UK).

The significance of election and referenda results are dangerously open to interpretation and manipulation by authorities. By providing more information QV has the potential to allow communities of people to better understand what vote results say about their values and intentions.

All participants receive the same limited number of voting credits that they can distribute to express nuanced preferences. For this reason, voters only use their voting credits on things that matter to them. The quadratic system also enables participants to express the intensity of their preferences for all options, but it costs them proportionately (quadratically) more credits to express strong feelings. (See table)

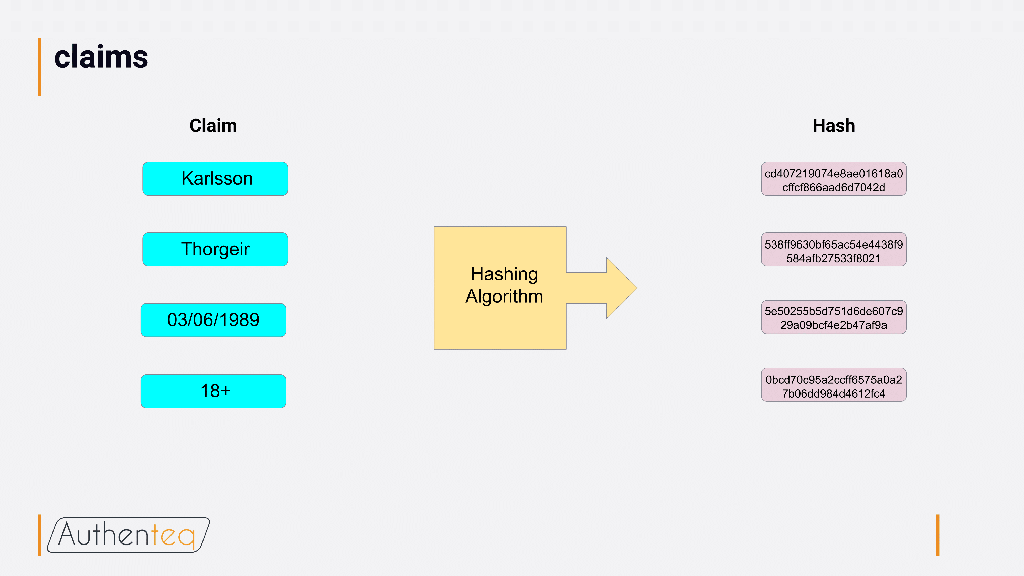

The CultureStake system will store voting data about each artwork on the Ethereum blockchain (a cryptographically secured distributed database) to guarantee ongoing access to tamper-proof public data.

CultureStake tests the ability of QV on the blockchain to produce trusted voting data – secure, transparent, and permanent – about culture experienced in places.

> Voting creates communally-owned information about what matters to people on the culture that happens in places.

> Voting contributes to shared knowledge about collective preferences, attitudes, and values.

CultureStake Software is published under a GNU Affero General Public License v3.0 AGPL-3.0

Main Repository URL: https://github.com/lazaruslabs/culturestake

Smart Contracts Repository URL: https://github.com/lazaruslabs/culturestake-contracts

Subgraph Repository URL: https://github.com/lazaruslabs/culturestake-subgraph

Infrastructure Provisioning URL: https://github.com/lazaruslabs/culturestake-provisioning

CultureStake is a DECAL/Furtherfield project.

Concept by Ruth Catlow, Charlotte Frost & Marc Garrett. Contributions by Sam Hart, Irene Lopez de Vallejo, Gretta Louw, Rhea Myers, Stacco Troncoso, and Ann Marie Utratel.

Technical development by Sarah Friend & Andreas Dzialocha.

Visual identity by Studio Hyte

Interview by Ruth Catlow

Transcribed by Anna Monkman

Ingrid LaFleur is on a mission to ensure “equal distribution of the future”. The curator of Manifest Destiny in Detroit, she also recently stood for mayor with an Afrofuturist manifesto.

Detroit has long played a critical role in the history of ‘domestic and global labor struggles.’

And now its quest for social justice has an avant-entrepreneurial dynamic, working across art, politics and technology. Activists respond to the city’s (often highly racialised) political failures to provide basic utilities with impressive social innovation. The recent boot-strapping community mesh networks for instance, was a response to the fact that 40 percent of Detroit residents have no access to the Internet at all. The alliances and networks formed in this project are now providing the social grounding for peer-to-peer technical education and experimentation with emerging decentralisation technologies. DACTROIT (an EOS project) is now exploring how payment for this infrastructure might be made through a community token.

I first interviewed LaFleur in July shortly before Detroit Art Week and the opening of Manifest Destiny at Library Street Collective Gallery.

Ruth Catlow: I have wanted to talk with you for a while about your current curatorial work. But first I think it’s worth noting that we share a number of unusual preoccupations. We are both inspired by the social justice sci-fi of Octavia E Butler; we root our work in locality; and have experimented with blockchain technologies as a site for artistic experimentation and social change. I have not however, stood for mayor. You have, and we will come to that later.

Please can you start by telling us about your exhibition Manifest Destiny.

Ingrid LaFleur: I only curate once every two or three years, almost like a museum curator. Manifest Destiny is a culmination of things that I have been thinking about for a while. Working across art and blockchain technology I’ve been very action-oriented thinking about what we need to be implementing, learning, adapting, innovating, in order to basically get free – that’s the whole point of my work.

I’m constantly trying to figure out how Black bodies can be free, which means I really need everyone to be free. And so I’m constantly unpacking, dissecting Afrofuturism as a framework or launchpad. I’m working to see what I’m missing, where are the gaps and how can I fill them in so that we can then make pathways forward and develop the futures that we really want to see. The exhibition title comes from this work.

I wanted to look at this in an abstract way. For instance, the painting series by Satch Hoyt, The Course of Stars of the Sirius System, are illustrating the star Sirius constellation, ground us in an ancient history which I think is very important as we plan and create these processes for manifestation. Satch Hoyt’s painting, Afro-Sonic Map (Black Mapping), is looking at how sound has been cultivated and informed by the different places through which it has travelled. And I’m pulling this interpretation out, because I believe that as we are imagining our destinies we have to be grounded in ancestral wisdom and Afro-Sonic Map (Black Mapping) reminds us of that ancestor from which the sounds are coming… But how they’ve also been wonderfully altered and transformed as a result of coming in contact with different realities – meaning that different times and history have informed the music, have informed how we are communicating sonically.

So this is a type of time travel, but it is not just time, it is realities, places and environments and all of these things that inform the work and how there is still always this thread that can always lead back to the original.

And in speaking of the original, the exhibition begins with an Afrofuturist boutique called DINKINESH. I created it because I really wanted to be able to provide items that were affordable and Afrofuturistic. One of the issues that I am having especially when it comes to Afrofuturist imagery is that it is very digital. I am here to bring it out into a physical space and make it both portable and affordable so then people can have it in their homes, place of work, wherever in the physical realm. The whole purpose of Afrofuturism is to shift consciousness and so I want it to be as available as possible. DINKINESH means “you are marvelous” and it is the name that was given to the oldest human remains found thus far, and they were found in Ethiopia. So this store is greeting you, it’s welcoming you into this space, but it’s also a gentle reminder that we all come from this one woman who is in, what we call now, Africa. And we are united by her. So DINKINESH initially will have this Afrofuturistic focus but over time it will grow to include Chicanofuturism and Indofuturism and all the futurisms of Black bodied and Brown bodied people. I am working on the boutique with Utē Petit who is based in New Orleans but from Detroit. He is designing the space and he is using imagery of flora from the Ethiopian region where Dinkinesh was found. The flora has been woven into the wallpaper for the space, so that is really exciting. I am very excited about DINKINESH.

RC: So people will be able to buy Afrofuturist art in the boutique.

ILF: Yes, like digital prints

RC: And will they be buying work that relates to work across the whole show?

ILF: Not really. Some of the artists will have products in the store like zines, hand-printed bags, but they were curated separately from the exhibition.

RC: This is work produced by just one artist or a group of people?

ILF: It’s literally like a retail store so it is work by a lot of different people. It’s like a museum store so it’s a lot of different people from all over. I am basically trying to gather it all together into one space. We don’t currently have one physical store to go and buy Afrofuturist anything.

RC: Wow! How have you sourced all of this? Is it all Afrofuturist art?

IF: Yeah, it’s a combination of people that I have been following online, or different groups that I have heard about, some of my friends might have items that I like, I know some of the artists personally, so it’s a variety of things. It is great, it is exciting, and slightly overwhelming- because it will keep going. To live on, beyond this exhibition.

RC: How will it live on afterwards?

ILF: We’re going to be popping up in different places, I can’t announce it yet. I imagine that each place will offer different kinds of experiences. There will be some augmented reality involved in this iteration. I want to grow that, and expand into virtual reality experiences.

RC: I can see why that would be a bit daunting, because if it’s a boutique and people will be buying things it means you will need to keep it stocked.

ILF: It’s a real store!

RC: And are you selling things on the blockchain?

ILF: That might become complicated. But eventually I do want to accept crypto once I find a point of sale system I feel comfortable with. But first, right now, I just need to understand what it means to have a retail space.

RC: To come back to Manifest Destiny, Can you tell us a little bit about the title of the exhibition? What’s the context and significance of Manifest Destiny as a phrase or as a name?

ILF: I am looking at what does it take to manifest one’s destiny. So as I mentioned before, the guidance of ancestral wisdom is really important, otherwise the possibilities of the past become inaccessible in the present. I’ve also learned, as we move into working with new technologies like blockchain, and the philosophies that are behind it, and becoming more familiar with the tech industry in general, how important it is that the planning phase should be a heart-led process. We can see how a person’s perspective is really going to affect the tech and how it interacts with the world and so I’ve become very sensitive to how we’re planning and approaching a thing in order to manifest it.

And then finally there are the tools to make the physical thing and that’s when I get really excited. Implementation.

RC: OK So can you talk me through the exhibition?

ILF: Yes, so it starts off with DINKINESH. Then it goes into Hyphen Labs’s NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism project which recreates a Black hair salon where you are getting your brain optimised. This is like that beginning process. And I think of the optimisation process as a way of decolonising because you don’t want to plan something that is a result of a colonised, limiting, narrow kind of perspective that is really based on someone else’s agenda. So you want to clear that and clean that up. Then Satch Hoyt’s beautiful paintings, Afro-Sonic Map (Black Mapping) and The Course of the Stars of the Sirius System. These give a reminder of the foundation of histories and ancient ancestral lineage. Then Alisha B. Wormsley created this really wonderful installation that is connecting the two gallery spaces. We also have her billboard that is placed outside of the gallery space above a bar right by public transportation, that says ‘There Are Black People In The Future’. I’m really excited about that because downtown Detroit has become 90% white even though the city is 85% Black so it’s like a little colony. The billboard is disrupting that space.

In the second gallery we have Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes has created a black and white film called Sacred, which is accompanied by a gorgeous sound that creates an ethereal multi-reality. Sacred is hard to talk about without giving away the mystery that’s embedded in it, but the thing that is sacred, you come to understand is sacred to us all. He has also created two sculptures that expresses the continuum that is necessary for the evolution of the future. And then there is Jasmine Murrell who created a collage tapestry, one of them titled Walking Time Travelers: Future will remind you of what is most important, what was lost, what was stolen, and what can never be replaced. Jasmine also created a deconstructed sculptures of hands that are coming through from a different reality.

That second gallery space opens up to an alleyway that has been fully renovated where there are clubs and restaurants and bars and all types of artwork, there will be five very large panels that will have augmented reality artwork. This work is coming from the Digitalia exhibition that was shown in San Francisco at the Museum of the African Diaspora, MoAD. I was such a fan of the exhibit that I invited Lady PheOnix who is the curator of Digitalia to travel a portion of the exhibition to Detroit. I was able to choose some images from that exhibition that is on display in the alleyway called The Belt. It will be up for a year. I’m very excited about this because not everybody is going to walk into the gallery space so this is a way of making the afrofuture a little more public, also because augmented reality is participatory it’s a fun activity that everyone can enjoy. For many this will be their first introduction to AR.

The last component of Manifest Destiny is the skills training through a series of workshops. The workshop programme includes a talk by Rasheedah Phillips who is known for her theoretical work on quantum futurism. The Black School reimagines the art school into a Black art school taught participants about ancient architectural techniques and fractals and then as a group built a pyramid. Creative technologist Onyx Ashanti held a 3-D printing workshop. And I gave a workshop on decentralizing power and new economies. The programme ends with DC comics writer Tony Patrick who led us into a worldbuild session over three days. We developed a vision for Detroit in 2040 that will become a comic and eventually a virtual reality experience.

RC: It sounds just amazing! Like there are a lot of different ways in for different kinds of people. How much do you think or care about who this is for and how they find out about it, and also what their experience of it is.

ILF: This show is literally for Detroiters. I am constantly thinking about the exhibitions, the materials, the exposure, making sure that Detroiters have exposure to what is happening in the entire world and I really don’t care if you have never been to a museum or if you go all the time. Most of my work has been directed towards people who might be in-between. They like art and are curious but maybe they are not going to gallery exhibitions all the time or following museum shows. I am very much aware that the gallery space is on the alleyway, The Belt, which is party central for downtown, day and night in the summer. What I love is part of the exhibition in the gallery is visible in The Belt because one of the walls is all window. Downtown attracts all kinds of people, definitely people who have probably not experienced as much artwork by Black artists in their life and who might be a little afraid of Black bodies and hopefully they can develop a new relationship based on this show.

I’m very clear with artists about where they are showing, the politics of what’s going on and who’s going to come through those doors, because some artists might be sensitive to this. Some artists might want to engage in a very particular way as a result. One artist wanted to do something a little more artistic that would work in MOMA, and I was there with him, I got it, but I was like, I just want you to understand that the people who are going to come through these doors have been day drinking. They are going to be in shorts and flip flops, like ‘oh this looks cool’ and ‘oh this is great’ and within minutes they are gone. To help ease people into the space I asked for black carpeting on the floor because I want people to pause when they enter, I want the hushness when you come in so you are a little more reflective. This did happen but also what I did not expect is how people then felt comfortable to sit and chat on the carpeted floor. That warmed my heart. I love when a traditionally austre space becomes an inviting one.

RC: So we run a gallery in the heart of a public park in North London, so we also get the day drinkers, and we also welcome the day drinkers! So it’s interesting to hear you talk about this.

RC: Given that Furtherfield has a readership from all over the world, I imagine that many people will not really have a sense of Detroit. So it would be great to hear you talk about why it’s important to you that this is happening in Detroit. And why Detroit?

ILF: Detroit is going through a major transformation, and some of us are in the midst of it, some of us are making it happen, and then some of us are running behind watching it happen and trying to figure out where we fit in. There is really no reason to leave anyone behind. It’s a critical moment because we are getting an influx of white people moving into a majority Black city. White people in the United States of America are not used to being minorities. Being a minority in their minds mean they have less power. It seems like they are saying to themselves, ‘I’m not used to being the only white person in a room so I’m going to stick with all the gentrified places where I remain majority in the room and I feel safer, more comfortable’. But what that means is that they are still not confronting their fear of Black people so it’s like they’ve decided to live in a tiny hut in a big forest and won’t explore the forest even though it offers new insights and experiences. And it’s ok if that’s what they really want, but then don’t stare or become hostile because Black people have entered a space.

My presence as a Black person can be very disruptive in these spaces, it’s like people forget that they are in a majority Black city. Nobody really cares when there are white people walking into a majority Black bar. The reason we don’t care is because we are in our safe space so a white person coming in is like [shrugs]. But when a Black person enters a majority white space a mixed bag perspectives awaits–a sprinkling of Trump supporters or a sprinkling of racists. A Black person has to figure it out in real-time constantly, whereas a white person coming into a Black space we are just like, ‘do you want a drink?’ It’s not like ‘Where are you from?’, ‘Why are you here?’. We don’t have it in us to do all the microaggressions that white people do and I really think it’s the lack of understanding Black people and culture that has caused a lot of harm. Also, the constant reinforcing of whites to separate themselves from people just because of the color of their skin, it’s dehumanising, causing a level of fear and depression that then becomes violent.

This exhibition is my way of confronting the anti-Blackness and making people face their fears, see it and think about it. What does it mean? Why is there a sign that says ‘There Are Black People In The Future’? Why is it even necessary to say that? What does that make me feel? What does that make me see in the future? And then it makes you question, how was I imagining the future? Did I imagine Black people there? Was I just imagining me and my people? It’s very much confrontational but in a very loving way and that’s why I put DINKINESH, our mother at the beginning.

RC: You talk about confrontation but you are also confronting the fear. So you are recognising what’s at play not just at the surface, but on many levels here.

ILF: Exactly. You cannot heal that which you do not acknowledge exists, so I need people to confront the fact that the fear exists somewhere, subconsciously, in your DNA, your heart. Once the fear is acknowledged, the healing begins and then liberation is close. But the problem in the United States is that whites don’t have to confront their fears. But what is misunderstood is how by not confronting fear they are limiting their own life, and they are denying themselves access to humanity.

RC: The first time I met you was at The Gray Area festival when you were talking about running as mayor with an Afrofuturist manifesto. I love that I can now wrap up this interview with a question about your political career!

ILF: Yes! I was the first political candidate to use Afrofuturism as a framework in a mayoral campaign. It was very much of a process to understand what it means to be an Afrofuturist within a political sphere because it had never happened before.

RC: And we should also look for the connection between your work with Decentralised Detroit and your curation of Manifest Destiny?

ILF: As I stated before, I have been in a space of action and because I am an impatient person and I would love to see everyone liberated and happy in my utopia while I am alive, I began investigating ways to tackle the poverty issue in Detroit. It was after I proposed a universal basic income using a cryptocurrency Detroit would create that I began exploring how cryptocurrency and blockchain technology allows for the development of new economies and ways to make money but how it is a tool allowing for efficiency when creating and building with people. Anybody who has worked in groups understands we need as much organization as possible so as a result of working with blockchain technology I’ve come to learn about decentralised autonomous communities and that’s when I become really excited. This is my Afrofuturist self trying to figure out what are the obstacles that Black bodies face in imagining futures, new futures, decolonised futures, futures of their own making from the desire of their own heart, not because of someone else’s agenda or brainwashing.

There are a lot of obstacles but I’ve come naturally and organically to a point where I decided to focus on economics. And so economic justice has been my centre point for a couple of years now. By really attending to the racial wealth gap (it would take the average Black American family approximately 228 years to accrue the wealth of the average white American family), we will then be able to see people have more control over their lives and the neighborhoods they live in. Now we have a pathway for growing wealth, which was something that was denied to Black Americans for over 400 years and continues today.

For me everything is always related, all of it, the art, the blockchain, everything. I am trying to attend to the mind, body, and soul, all at the same time. It is hard for me to focus on just one pathway towards liberation. I like to understand and be involved in multiple pathways to freedom. That’s what keeps me exploring, curating, teaching, lecturing and creating workshops.

Manifest Destiny, is curated by Ingrid LaFleur. It is now on view at the Library Street Collective Gallery until 5 October 2019

Curator, pleasure activist and Afrofuturist. Her mission is to ensure equal distribution of the future, exploring the frontiers of social justice through new technologies, economies and modes of government. As a recent Detroit Mayoral candidate and founder and director of AFROTOPIA, LaFleur implements Afrofuturist strategies to empower Black bodies and oppressed communities through frameworks such as blockchain and universal basic income. Ingrid LaFleur is currently the Director of Social Impact for Detroit Blockchain Center and curator of Manifest Destiny currently taking place at Library Street Collective in Detroit.

Join us in London at the DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’

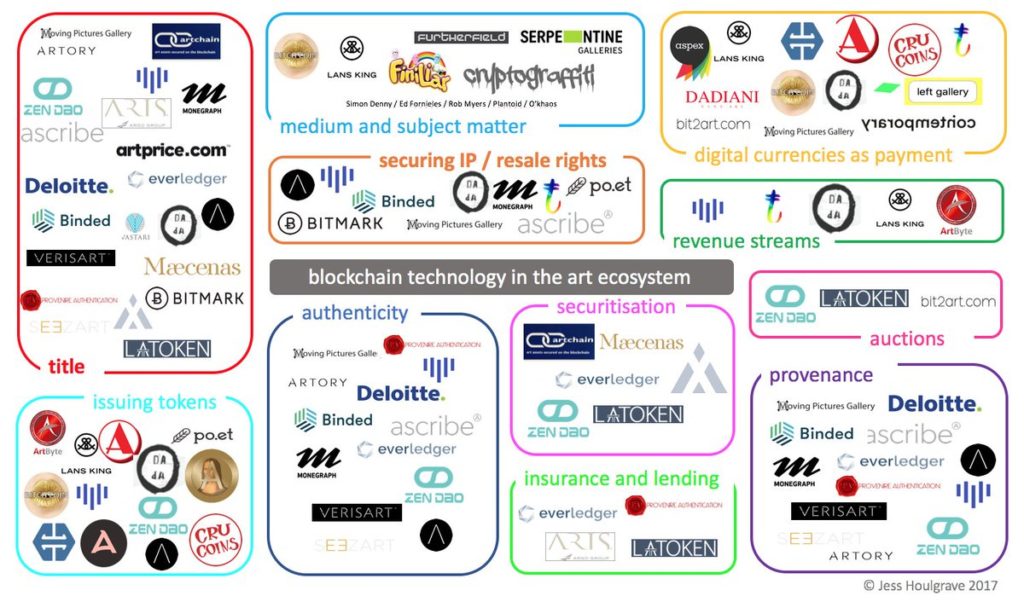

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

Discussion will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

9.00 Registration

9.30 Welcome and Scene Setting

State of the Arts: Blockchain’s Impact in 2019 and Beyond | A comprehensive overview of developments from critical artistic practices and emergent blockchain business models in the arts. DAOWO Arts and Blockchain pdf download (Catlow & Vickers 2019).

Presentation and hosted discussion with Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers

10.30 Coffee

10.45 Protecting the Rights of Indigenous Australian Artists. What part can Blockchain technologies play?

The Copyright Agency, Australia in conversation with Mark Waugh, DACS UK

11.30 Towards a Decentralised Arts Economy

The launch of Zien, the new dApp for artists will be followed by a presentation and panel discussion with Peter Holsgrove, and artists of A*NA around the implications of tokenising artistic practices.

12.15 Digital Catapult panel

12.45 Wrap up, takeaways and final discussion

Ruth Catlow, Ben Vickers & Mark Waugh

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow Co-founder of Furtherfield & DECAL Decentralised Arts Lab

Peter Holsgrove, Founder of A*NA

Ben Vickers, CTO Serpentine Galleries, Co-founder unMonastery

Mark Waugh, Business Development Director DACS

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL Decentralised Arts Lab initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership DACS, UK.

Furtherfield has worked with decentralised arts and technology practices since 1996 inspired by free and open source cultures, and before the great centralisation of the web.

Visit DECAL website

10 years ago, blockchain technologies blew apart the idea of money and value as resources to be determined from the centre. This came with a promise, yet to be realised, to empower self-organised collectives of people through more distributed forms of governance and infrastructure. Now the distributed web movement is focusing on peer-to-peer connectivity and coordination with the aim of freeing us from the great commercial behemoths of the web.

There is an awkward relationship between the felt value of the arts to the majority and the financial value of arts to a minority. The arts garner great wealth, while it is harder than ever to sustain arts practice in even the world’s richest cities.

In 2015 we launched the Art Data Money programme of labs, exhibitions and debates to explore how blockchain technologies and new uses of data might enable a new commons for the arts in the age of networks. This was followed by a range of critical art and blockchain research programming:

Building on this and our award winning DAOWO lab and summit series, we have developed DECAL – our Decentralised Arts Lab and research hub.

Working with leading visionary artists and thinkers, DECAL opens up new channels between artworld stakeholders, blockchain and web3.0 businesses. Through the lab we will mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies to experiment in transnational cooperative infrastructures, decentralised artforms and practices, and improved systems literacy for arts and technology spaces. Our goal is to develop fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

For more see our Art and Blockchain resource page.

Join us in Edinburgh at the first DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’ of 2019

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

This summit will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

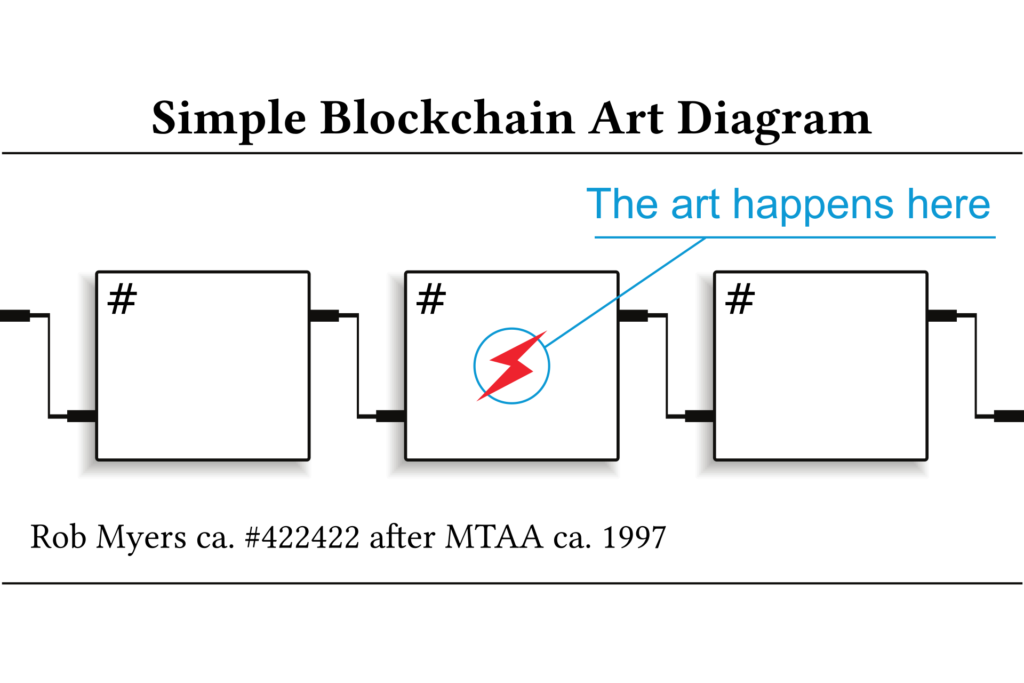

Although the term ‘blockchain’ has trickled downstream into the public domain, the principles behind the technology remain mysterious to many. Embodied within physical assemblages or social interventions that mine, hash and seal the evidence of human practices, creatives have provided important ‘coordinates’ in the form of artworks that help us to unpick the implications of the technology and the extent to which it re-configures power structures.

Hosted by Prof Chris Speed and Mark Daniels with panellists:

Pip Thornton – The Value of Words in an Age of Linguistic Capitalism

Bettina Nissen & Ailie Rutherford – Designing feminist cryptocurrency for Govanhill

Evan Morgan – GeoPact

Jonathan Rankin – OxChain, Pizza Block

Larissa Pschetz – Karma Kettles

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield and DECAL

Mark Daniels, New Media Scotland

Clive Gillman, Creative Scotland

Marianne Magnin, Arteïa

Prof Chris Speed, Design Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Ben Vickers, Serpentine Galleries

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership with the Department of Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh and New Media Scotland.

OxChain is a major EPSRC research project which explores how Blockchain technologies can be used to reshape value in the context of international development and the work of Oxfam, involving the Universities of Edinburgh, Northumbria and Lancaster.

When I first heard about MoneyLab, it was back in 2013 or the beginning of 2014, when I was doing my masters in London. A friend of mine handed a flyer to me and I was intrigued by the strange typography and the combination of bright colours. However, I didn’t quite believe that any kind of initiative could really start an alt-economy movement. Not that I didn’t believe in local currency or creative commons, but those gentle approaches generally seemed to lack traction, just like liberals do with voters. I naturally thought MoneyLab was one of those initiatives.

However, as Bitcoin was becoming a hype, the name popped up again; MoneyLab itself was also becoming a hype. While bitterly regretting not being able to be associated as the first wave of participants, I started to think that maybe MoneyLab might be the framework that can really push out alternative economic attempts as mainstream culture. My stance towards economic shifts was somewhat similar to that of William Gibson’s; he said in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, ‘What would my superpower be? Redistribution of wealth’. How did that change after reading the MoneyLab Reader 2?

Before going into the details of what blockchain technology can really do, it is crucial to understand a new “unit of value” created in modern society (Pine and Gilmore 1999). Since the most prominent piece of technology of our era is undoubtedly smartphones (with Apple being the first 1 trillion dollar publicly listed company in the US), a lot of transactions are inevitably conducted through apps and web services. The proliferation of the so-called “payments space” signifies the era of UX design, which is the third paradigm of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction), “tak[ing] into account…affect, embodiment, situated meaning, values and social issues” (Tkacz and Velasco 2018). In other words, experience has become the deciding factor of customers’ choices. With vast amounts of data generated at the back of sleek interfaces, one can precisely oversee the users’ behaviour, which then is fed back into the system.

All the payments spaces are essentially digital. This means transactions leave digital traces whether you like it or not. The idea of a cashless society exactly stems from this interest, the authorities can have better understandings of how people make money; in other words, where black money flows. Brett Scott has been pointing out the danger of a cashless society for quite some time now, I saw another variation in this book.

According to Jaya Klara Brekke, blockchain technology can make money programmable, “allow[ing] for very fine-grained (re)programming of the medium of money, from what constitutes, and how to measure, value-generating activity to the setting of parameters on the means and conditions of exchange – what is spendable, where and by whom” (Brekke 2018). The overall impression I got from the MoneyLab Reader 2 about what blockchain technology can really do is basically this. Making a currency programmable using smart contracts.

More than a couple of authors discuss how “contingency” should take place in designed currencies. Contingency is different from randomness; in fact, it could mean exactly the opposite. For example, when coins are distributed in a perfectly random manner, you have absolutely no control in the handling process. If contingency is embedded in a system, it means there are exploitable gaps, which seem to almost randomly benefit people. On the other hand, some individuals would find ways to make use of these gaps, which are considered to be legitimate. Brekke discusses how the way in which contingency is programmed into a currency will be a key for the future of finance, both in terms of experience and redistribution of wealth. Therefore, currency designers will be the next UX designers.

A number of ideas applying blockchain technology to both physical and cultural objects are mentioned in this book, from a self-maintaining forest to blockchain-based marriage. “Terra0” is the concept of an autonomous forest which can “self-harvest its own value” (Lotti 2018). Utopian views of a human-less world are prevalent, but in reality, a healthy forest requires an adequate amount of human intervention. In addition, the value of a forest cannot be determined by itself; trade routes, demand and supply, they are all drawn by human movements. For example in Japan, domestic wood resources are generally not profitable because of the expensive labour costs. Illegally cut trees without certification from Southeast Asia dominate the market, putting domestic ones in a bad position. When a forest itself is not profitable, how can it accumulate capital autonomously? Besides, the oracle problem has not been discussed at all. Unless everything is digital in the first place, there always needs to be somebody to put data onto the blockchain. In other words, the transcendence of the boundaries between the physical and the digital is not possible without human intervention. Blockchain marriage would face a similar problem; who might be the witness if circumventing the government official? Max Dovey investigates the notion of “crypto-sovereignty” while introducing an example of a real blockchain marriage where they “turn[ed] ‘proof of work’… into ‘proof of love’”(Dovey 2018). Just as the sacramental bond between spouses can be broken before Death Do Them Part, so can any cryptographic marriage unravel despite having been recorded in an immutable ledger. Whatever repercussions may exist for divorce, there are no holy or technological mechanisms to prevent it.

Platform co-ops is one of the largest topics in the book besides Universal Basic Income (UBI). A platform co-op is often a cooperatively owned version of a major platform that is supposed to be able to pay better fees to the workers. Also, a platform co-op is often associated with “lower failure rate”; 80% of them survive the first five years when only 41% of other business models do (Scholz 2018). While embracing the positive aspects of platform co-ops, I have this question stuck in my head: can you not make a platform co-op based on a new idea rather than copying existing ones?

Most platform co-ops seem that they are looking at already successful and established concepts such as rental marketplaces for rooms and ride hailing services. As a result, platform co-ops are considered more to be a social movement than an innovation. Why not just run a business right at the centre of Capitalism without being motivated by profit? Many platform co-ops challenge the main stream services such as Airbnb or Uber, however those services operate based on scale; if they have the largest user base, it will be very difficult to take them on, unless they die themselves like Myspace… Moreover, more hardware side of development can be happening around co-ops, but I don’t hear anything except for Fairphone. When can I stop using my ThinkPad with Linux on it?

After reading the MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype, now I’m thinking of how I should design my own currency. Of course whether cryptocurrencies are actually currencies is up to debate; depending on who you ask, Ethereum is a security (SEC), a commodity (CFTC), taxable property (IRS) or a currency (traders).

MoneyLab 2 authors overall suggest that we should not limit our imagination to fit in the existing finance systems, but think beyond. You don’t necessarily need to cling to cryptocurrencies but they may help you shape your ideal financial system.

At Furtherfield we have worked with decentralised network practices in arts and technology since we published our first webpages in 1996 – before the great centralisation – when the web thought it was already distributed and P2P. We took the spirit of punk and DIY in a more collaborative direction inspired by Free and Open Source Software methods and cultures, to build new platforms and art contexts with a playful Do It With Others (DIWO) ethos. We still connect with artists, techies, activists and thinkers from our base in Finsbury Park in North London, and internationally online. In 2015 Furtherfield launched the Art Data Money programme that sought to develop a commons for the arts in the network age.

DECAL – Decentralised Arts Lab is the outcome.

DECAL exists to mobilise crowdsourced research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies now.

Furtherfield Spring Editorial 2018 – Blockchain Imaginaries

2018

Introduction to Furtherfield Spring season of art and blockchain essays, interviews, events, exploration and critique.

Collected writings by Rhea Myers

2014 – Present

On blockchain geometries, accelerationist art, crypto and DAWCs, art for algorithms, and (Conceptual) Art, cryptocurrency and beyond.

DAOWO – The blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts

Oct 2017 – Present

A temporary laboratory for the creation of a living blockchain art laboratory devised by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with Goethe Institut, London.

New World Order

2017 – 18

Artists envision a world made by machines, markets and natural processes, without states or other human institutions in an international touring exhibition curated by Furtherfield.

Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain

2017

The first book of its kind, bringing together artistic, speculative, conceptual and technical engagements with blockchains.

Edited by Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Nathan Jones, and Sam Skinner

Jaya Klara Brekke: I saw the Blockchain at the End of The World, turned around, and walked back

2018

Written on the occasion of the New World Order group exhibition for PostScriptUM #31 Series published by Aksioma, edited by Janez Janša

Blockchain Art Commission*

2017

Clickmine by Sarah Friend is a hyperinflationary ERC-20 token that is minted by a clicking game.

A Furtherfield and NEoN Digital Arts Festival Co-commission

Ethereal Summit NY

2018

Commission and exhibition of contemporary artists working with public blockchains as a medium for conceptual and social experimentation. Jurors and curators, Ruth Catlow, Giani Fabricio, Sam Hart, Will King, Saraswathi Subbaraman

The Blockchain: Change Everything Forever

2016

A short film to stimulate cross sector debate around how emerging blockchain technologies change the social contract, directed by Pete Gomes

Role Play Your Way to Budgetary Blockchain Bliss

2016

Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers brought the LARPing tradition to INC’s MoneyLab. Inviting participants to take on generic roles from the business cycle of start up tech companies trying to make the next big thing with the latest technological innovation.

Blockchain’s Potential in the Arts

2016

A gathering of organisations, academics and policy makers in arts and culture to explore blockchain’s potential. Convened by Ben Vickers and Ruth Catlow and hosted by the Austrian Cultural Forum, London.

The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies

2015

An exhibition curated by Futherfield to explore how might we produce, exchange and value things differently for a transformed artistic, economic and social future?

http://rhizome.org/editorial/2018/jun/14/island-mentality/

https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/cryptokitty-blockchain/index.html

http://hyperallergic.com/440936/what-blockchain-means-for-contemporary-art/

https://www.artbasel.com/news/artists-as-cryptofinanciers–welcome-to-the-blockchain

Exhibition, Furtherfield Gallery, London Oct 2015 – Nov 2015

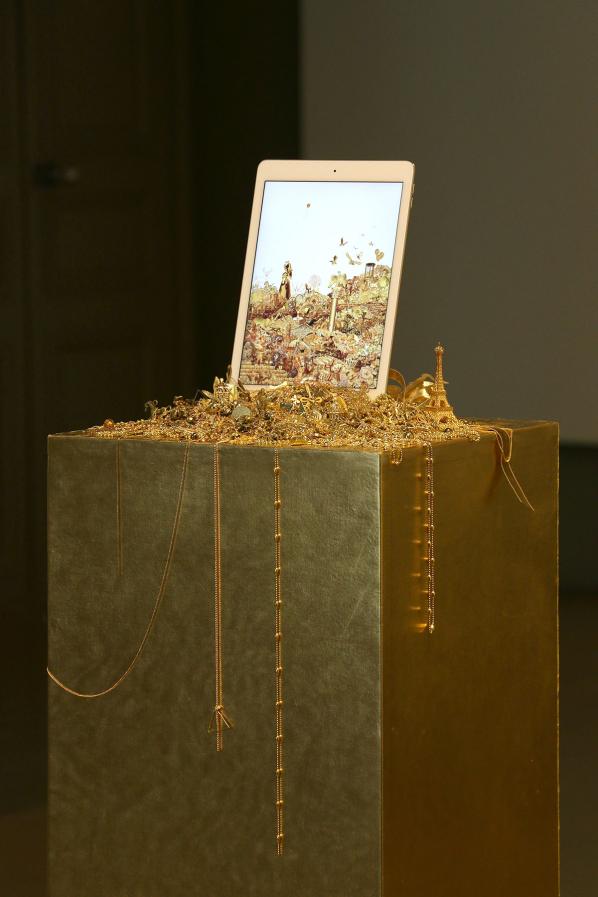

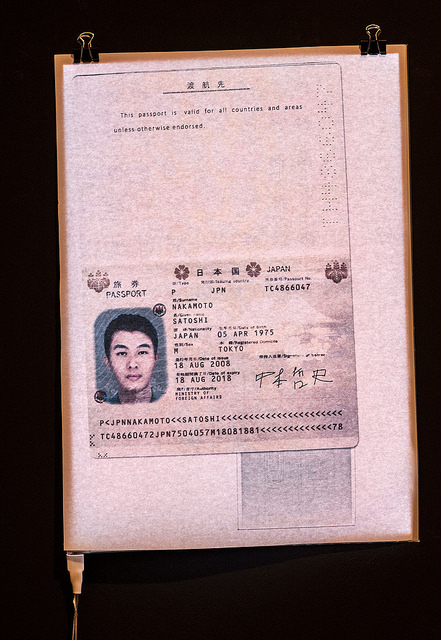

Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion exhibit ornamental Gold and Glitter created with ‘found’ internet GIFs and Nakamoto (The Proof) – a video documenting the artists’ attempt to produce a fake passport of the mysterious creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto. FaceCoin by Rhea Myers is an artwork that is also a machine for mining faces as proof of aesthetic work. His Shareable Readymades are iconic 3D printable artworks for an era of digital copying and sharing. The Museum of Contemporary Commodities by Paula Crutchlow and Dr Ian Cook treats everyday purchases as if they were our future heritage and Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc reclaims ownership of personal data by turning her entire being into a corporation. The Alternet by Sarah T Gold conceives of a way for us to determine with whom, and on what terms, we share our data and Shu Lea Cheang anticipates a future world where garlic is the new social currency.

Press:

JJ Charlesworth for Art Review Jan-Feb 2016

Short film, 2016

The underpinning technology of digital currencies and smart contracts, the blockchain is reshaping concepts of value, trust, law and governance. This film sets out to diversify the people involved in its future by bringing together leading thinkers, computer scientists, entrepreneurs, artists and activists who discuss:

A Furtherfield film with Digital Catapult London. Directed by Pete Gomes, concept and research by Ruth Catlow. Featuring interviews with: Dr Anat Elhalal; Ben Vickers; Dr Catherine Mulligan; Elias Haase; Irra Ariella Khi; Jaime Sevilla; Jaya Klara Brekke; Kei Kreutler; Pavlo Tanasyuk; Rhea Myers; Sam Davies; and Vinay Gupta

Live Action Role Play, 2016

This 2-day start up tech hackathon compressed into 2 hours was aimed at creating Blockchain based businesses ideas that improve the life and future of cats. The workshop critically emulated the extravagant discourse and excitement surrounding the super-automation and hyperconnectivity that comes with blockchain and similar technologies, and the capacity of the technology stakeholders to both increase and diminish global inequity. Devised by Ben Vickers, Ruth Catlow for Institute of Network Cultures’ MoneyLab.

Report:

http://networkcultures.org/moneylab/2016/12/06/role-play-your-way-to-budgetary-blockchain-bliss/

International Touring Exhibition, 2017 – 2018

Jaya Klara Brekke, Max Dovey, Pete Gomes, HandFastr, Rhea Myers, Primavera De Filippi of O’Khaos, Terra0, Lina Theodorou and xfx (aka Ami Clarke). Curated by Furtherfield

A self-owning forest with ideas of expansion, a self-replicating android flower, a cryptocurrency rig to mine human breath, a five minute marriage contract, a Hippocratic Oath for software developers; in an exhibition about living with blockchain technologies.

Artists investigate and test the possible consequences of blockchain technologies, and their capacity to embody divergent political ideas. They explore dramatic new conceptions of global governance and economy, that could permanently enrich or demote the role of humans. They portray a world in which responsibility for many aspects of life are transferred, permanently (for better or worse) from natural and social systems into a secure, networked, digital ledger of transactions, and computer-executed contracts.

Produced as part of the State Machines programme*

Press: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/cryptokitty-blockchain/index.html

Book published by Torque Editions, 2017

Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain is the first book of its kind, intersecting artistic, speculative, conceptual and technical engagements with the the technology heralded as “the new internet”. The book features a range of newly commissioned essays, fictions, illustration and art documentation exploring what the blockchain should and could mean for our collective futures.

Artists Re:Thinking The Blockchain

Imagined as a future-artefact of a time before the blockchain changed the world, and a protocol by which a community of thinkers can transform what that future might be, Artists Re:Thinking The Blockchain acts as a gathering and focusing of contemporary ideas surrounding this still largely mythical technology. The full colour printed first edition includes DOCUMENTATION of artistic projects engaged in the blockchain, including key works Plantoid, Terra0 and Bittercoin, THEORISATION of key areas in the global blockchain conversation by writers such as Hito Steyerl, Rachel O’Dwyer, Rhea Myers, Ben Vickers and Holly Herndon, and NEW POETRY, ILLUSTRATION and SPECULATIVE FICTION by Theodorios Chiotis, Cecilia Wee, Juhee Hahm and many more. It is edited by Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Nathan Jones and Sam Skinner.

Along with a print edition, Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain includes a web-based project in partnership with Design Informatics at University of Edinburgh: Finbook is an interface where readers and bots can trade on the value of chapters included in the book. As such it imagines a new regime for cultural value under blockchain conditions.

This book and surrounding events is produced in collaboration between Torque and Furtherfield, connecting Furtherfield’s Art Data Money project with Torque’s experimental publishing programme. It is supported by an Arts Council England Grants for the Arts, Foundation for Art and Creative Technology and through the State Machines project by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union.

Buy Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain

Format: Paperback

ISBN number: 978-0-9932487-5-7

Torque and Furtherfield, London, 2017

Distributor: Liverpool University Press

Press:

http://we-make-money-not-art.com/artists-rethinking-the-blockchain/

https://hyperallergic.com/440936/what-blockchain-means-for-contemporary-art/

http://networkcultures.org/moneylab/2018/01/26/artists-rethinking-the-blockchain/

The blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts, 2017 – Present

This series brings together artists, musicians, technologists, engineers, and theorists to join forces in the interrogation and production of new blockchain technologies. The focus is to understand how blockchains might be used to enable a critical, sustainable and empowered culture, that transcends the emerging hazards and limitations of pure market speculation of cryptoeconomics.

Devised by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with Goethe Institut, London.

Contributors include Ramon Amaro, Jaya Klara Brekke, Ed Fornieles, Jess Houlgrave, Janez Jansa, Helen Kaplinsky, Thor Karlsson, Kei Kreutler, Sarah Meiklejohn, Julian Oliver, Emily Rosamond, Hito Steyerl, Mark Waugh, Laura Willis.

Visit the DAOWO website to view video and pdf resources

Produced as part of the State Machines programme*

Press:

http://rhizome.org/editorial/2018/jan/03/reinventing-the-art-lab-on-the-blockchain/

http://rhizome.org/editorial/2018/jun/14/island-mentality/

*State Machines: Art, Work and Identity in an Age of Planetary-Scale Computation

Focusing on how such technologies impact identity and citizenship, digital labour and finance, the project joins five experienced partners Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY) together with a range of artists, curators, theorists and audiences. State Machines insists on the need for new forms of expression and new artistic practices to address the most urgent questions of our time, and seeks to educate and empower the digital subjects of today to become active, engaged, and effective digital citizens of tomorrow.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Artists Organise (on the blockchain) was the fourth event in the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts, in collaboration with Goethe Institut London.

In this special event, hosted by Drugo more in Rijeka we learned from the Croatian cultural context before envisioning, devising and testing alternative forms of blockchain-based cultural production systems, for application at Furtherfield in London.

We talked with Davor Miskovic about Clubture, the non-profit initiative that has distributed national cultural funding between a network of peers in Croatia since 2002 according to decentralised, participatory principles.

Workshop participants then took Julian Oliver’s Harvest, in which “wind energy is used to mine cryptocurrency to fund climate research”, as their focus for new proposals for blockchain-based projects to connect park-based arts venues with their local communities. Then they took turns to perform the role of a select committee of skeptical park stakeholders who wanted to know how park users would benefit from the scheme in a time of cuts to public funding and climate change.

Read the semi-fictional Minutes of the Bunsfury Park Stakeholders Group Select Committee

This special event, devised by Ruth Catlow and Max Dovey, and hosted by Drugo more formed part of a wider programme events in Rijeka to accompany the opening at Filodrammatica Gallery of the touring exhibition New World Order.

Thanks to all participants!

13.30 – 17.30 – Kei Kreutler, Sarah Meiklejohn, Laura Wallis, Jaya Klara Brekke

Doing Good (on the blockchain) is the third event in the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts.

In previous workshops we have probed ideas focusing on developments for blockchain application in the arts and the role of identity within the blockchain ecosystem.

Citizen groups that engage in activism and ‘doing good’ are generally structured around informal economies which rely on a certain degree of flexibility, improvisation and indeterminacy of activity. The introduction of technical systems can have a flattening effect that removes all contingency from a system. It sets distinct rules under which an activity or exchange can take place. These rules however can be somewhat opaque, shaped by the affordances of technologies rather than the needs of its users. This event aims to examine what is at stake in the formalisation of ‘doing good’ under blockchain systems for decentralised trust. We will look at how informal systems (e.g. for organising migration from war zones to stable territories) are forced into a formalised rule based structure, while formal systems for public good (eg distribution of social welfare) may exacerbate issues of both exclusion and monitoring. We consider design for contingency, and identify what must be left out.

The Right Systems For The Job?

Sarah Meiklejohn will set the scene sharing her research into developments in systems of decentralised trust, openness and visibility in finance, supply chains, and managing personal data.

This will be followed by 3 provocations that will inform discussion and debate:

Increased Engagement & Resisting De-facto Centralisation

Jaya Klara Brekke on the affordances of Faircoin blockchain technology, exploring its use as a redistribution of what is possible, and for who – extending and reconfiguring spaces and modes of politics.

Incentives for Participation

Laura Willis, on the work of Citizen Me – a platform that promotes the understanding of the value of personal data through notions of citizenship.

Behaviour under Transparency

Kei Kreutler (Gnosis) on blockchain’s potential ability to encode and incentivize social behavior, both on- and off-chain, and designing for unforeseen consequences. How does the figure of the good—politically and aesthetically—influence the uptake of “new” technologies, and how do staked predictions influence the present?

This workshop is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine) in collaboration with Goethe-Institut London and in partnership with Dr Sarah Meiklejohn from UCL, as part of the research project Glass Houses – Transparency and Privacy in Information Economies.

Sarah Meiklejohn

Sarah Meiklejohn is a Reader in Cryptography and Security at University College London. She has broad research interests in computer security and cryptography, and has worked on topics such as anonymity and criminal abuses in cryptocurrencies, privacy-enhancing technologies, and bringing transparency to shared systems.

Jaya Klara Brekke

Jaya Klara Brekke writes, does research and speaks on the political economy of blockchain and consensus protocols, focusing on questions of politics, redistribution and power in distributed systems. She is the author of the B9Lab ethical training module for blockchain developers, and the Satoshi Oath, a hippocratic oath for blockchain development. She is based between London, occasionally Vienna (as a collaborator of RIAT – Institute for Future Cryptoeconomics) and Durham University, UK where she is writing a PhD with the preliminary title Distributing Chains, three strategies for thinking blockchain politically (distributingchains.info).

Laura Willis

Laura Willis works as Design Lead in user experience at CitizenMe. Alongside this work Laura is also very passionate about illustration and won an award for Macmillan children’s books before she graduated from University of the Arts, London.

Kei Kreutler

Kei Kreutler is a researcher, designer, and developer interested in how cultural narratives of technologies shape their use. She contributes to a range of projects—from the networked residence initiative unMonastery to the augmented reality game for urban research PATTERNIST—related to organizational design and practice. She is Creative Director at Gnosis, a forecasting platform on the Ethereum blockchain, and lives in Berlin.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries & unMonastery) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

We are delighted to share with you our Spring season of art and blockchain essays, interviews and events, offering a wide spread of exploration and critique.

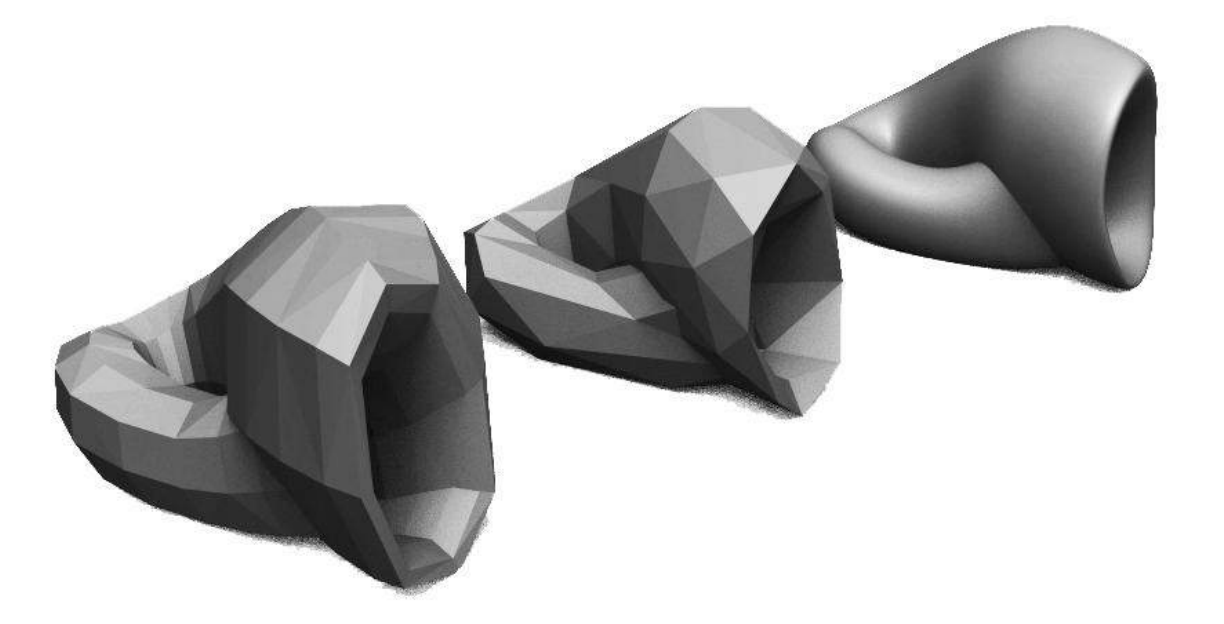

The blockchain is an evocative concept, but progress in ideas of cryptographic decentralisation didn’t stop in 2008. It’s helpful for artists to get a sense of the plasticity of new technical media. So first we are pleased to share with you Blockchain Geometries a guide by Rhea Myers to the proliferation of blockchain forms, ideas and their practical and imaginative implications.

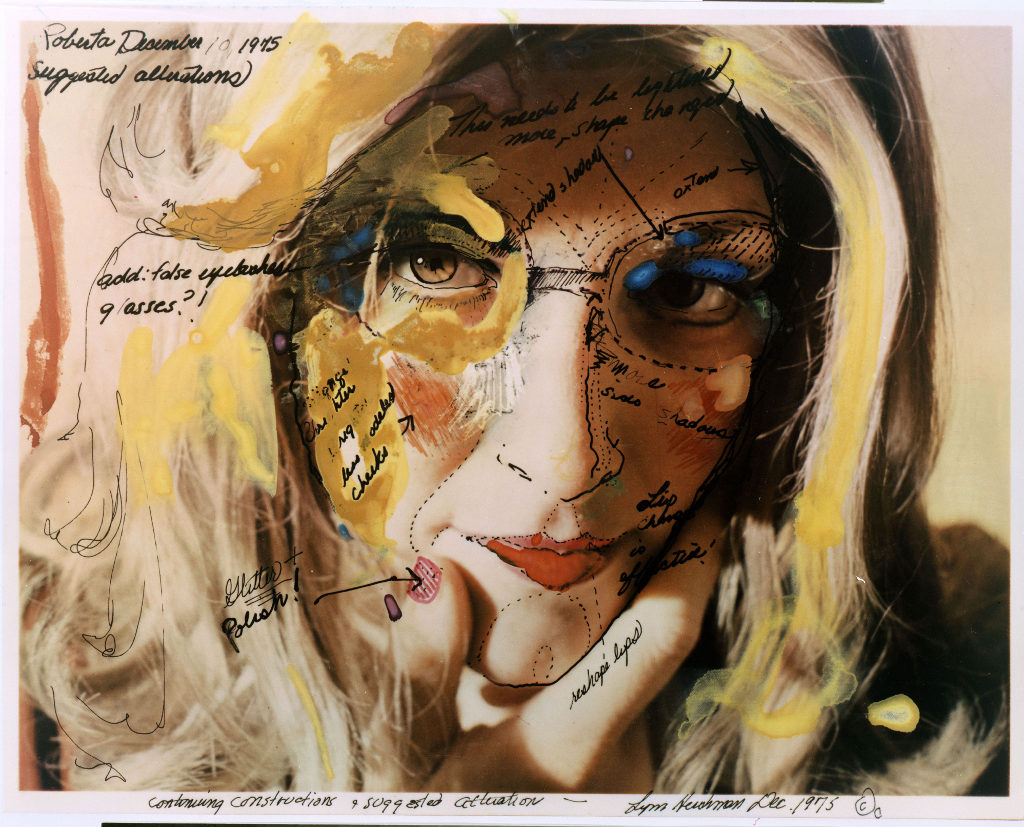

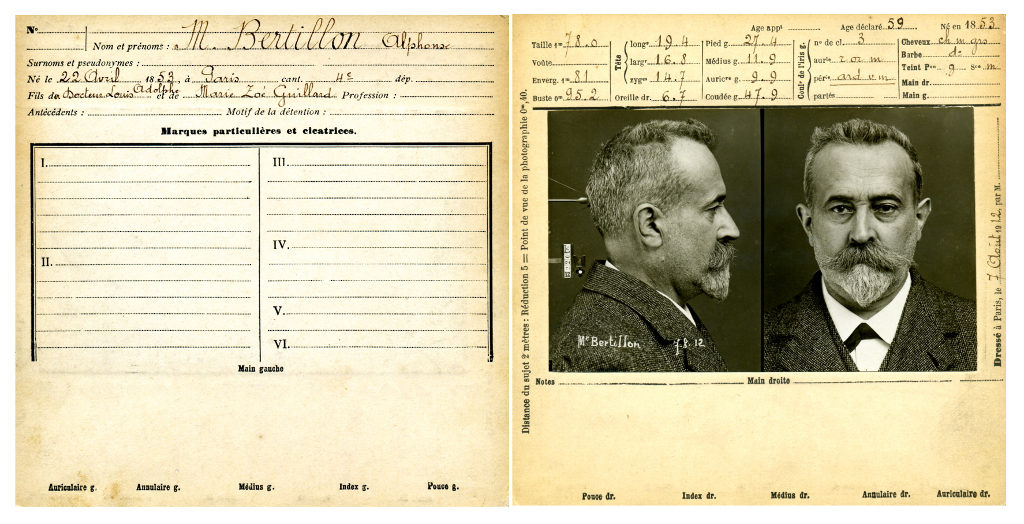

In Moods of Identification Emily Rosamond writes her response to our second DAOWO workshop, Identity Trouble (on the blockchain). She reflects on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon speak here with Marc Garrett in an interview republished from our book with Torque Editions Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain (2017). Mat and Holly convey a sense of excitement about developments and opportunities for new forms of decentralised collaboration in music.

Finally you can book your place on future events at the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts.1 Download the DAOWO Resource #1 for key learnings, summaries of presentations, quotes, photographs, visualisations, stories and links to videos, audio recordings and much more from our first two events about developments in the arts and the trouble with Identity.

The blockchain is 10 years old and is surrounded with a hype hardly seen since the arrival of the Web. We’d like to see more variety in the imaginaries that underpin blockchains and the backgrounds of the people involved because technologies develop to reflect the values, outlooks and interests of those that build them.

Artists have worked with digital communication infrastructures for as long as they have been in existence, consciously crafting particular social relations with their platforms or artwares. They are also now widely at work in the creation of blockchain-native critical artworks like Clickmine by Sarah Friend2 and Breath (BRH) by Max Dovey, Julian Oliver’s cryptocurrency climate-change artwork, Harvest (see featured image) and 2CE6… by Lars Holdhus3, to name but a few.

By making connections that need not be either utilitarian nor profitable, artists explore potential for diverse human interest and experience. Also, unlike on blockchains, where time moves inexorably forward (and only forward) – fixing the record of every transaction made by its users, into its time slot, in a steady pulse, one block at a time – human imaginative curiosity can scoot, meander and cycle through time, inventing and testing, intuiting and conjuring, possible scenarios and complex future worlds. They allow us to inhabit, in our imaginations, new paradigms without unleashing actual untested havoc upon our bodies and societies.