Feral Class Book out now!

Untamed, Unheard, Unstoppable… a moving memoir about being a working-class artist… Art on the Margins, Life Without Permission

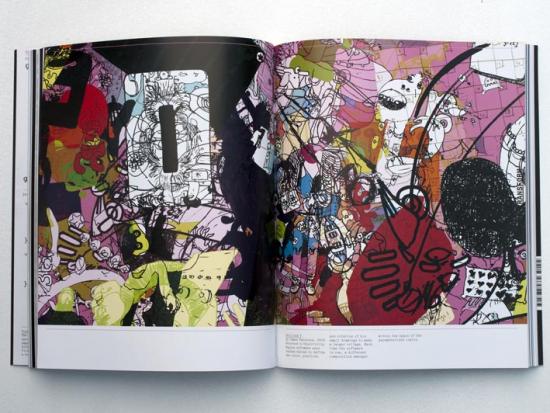

Furtherfield is thrilled to announce the release of Feral Class, a bold and deeply personal memoir by its co-founder, Marc Garrett. This powerful narrative chronicles his journey as a working-class artist navigating a system designed to exclude voices like his.

At Furtherfield, challenging the entrenched class inequalities of the art world has always been at the heart of our work. Today, as rising costs, hostile institutions, eroded social welfare, and dwindling opportunities push working-class artists to the margins, Marc’s story reminds us of the urgent need to uplift, fund, and amplify the next generation of working-class artists before their contribution is lost completely.

Feral Class is Marc Garrett’s deeply personal and thought-provoking exploration of his early years, chronicling his journey as a working-class artist navigating a world that often rejects them. Through humorous, vivid storytelling and incisive critique, Garrett explores how his upbringing shaped his identity, forging a path that defied societal expectations. How can one survive, let alone thrive, as part of what Garrett describes as the feral class: a group of individuals who, like him, exist outside traditional institutions and thrive in the margins, using resourcefulness and rebellion to carve out their own artistic spaces?

Weaving together personal memories, political reflections, and the struggles of working-class artists, Feral Class challenges the elitism of the art world. It celebrates the radical potential of those who refuse to conform. Garrett’s narrative is both an intimate self-portrait and a rallying cry for artists who refuse to be tamed. Passionate, unfiltered, and insightful, this book is an essential read for anyone interested in the intersections of class, creativity, and resistance.” Minor Compositions

Foreword by Cassie Thornton.

Ordering Information

For Ordering in the UK Only

Available direct from Minor Compositions (in the UK) for the special price of £13.

Pre-orders for the book will be taken during July 2025.

https://www.minorcompositions.info/?p=1561

Anyone who pre-orders the book directly from Minor Compositions during this month will receive a special, barcode-free version of the book with colour images (the regular trade version will be printed in greyscale). Advance orders to be shipped in August.

218 pages, 5.5 x 8.5, paperback

UK: £20 / US: $25

ISBN 978-1-57027-439-8

Release to the book trade 1 January 2026

Buy Now and use code: CSF19ASRA for a 30% discount

In India, the practice of jugaad—finding workarounds or everyday, usually non-technical hacks to solve problems—emerged out of subaltern strategies of negotiating poverty, discrimination, and violence. Yet it is now celebrated in management literature as ‘disruptive innovation’. In this book Rai considers how these time-efficiencies always exceed their role in neoliberal and authoritarian postcolonial economies and are put into motion by subaltern practitioners themselves.

On Sat 27 Apr from 14.00-16.00 Rai will introduce this important work to guests followed by a Q and A session with Furtherfield Co-Founding Director, Marc Garrett – with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park* and has been supported by the Borderlines Research Group in Creative Economies and Postcolonial Intersectionality at Queen Mary, University of London.

“This original and innovative work will enable a new and perhaps paradigm-shattering interpretation of the coimplication of digital assemblages, temporality, and affect. Drawing on a rich ethnographic archive, Amit S. Rai is deeply sensitive to how gender, class, and caste are implicated in emergent techno-perceptual assemblages. His invaluable book is also an effective antidote to the Eurocentricity of digital media studies.” — Purnima Mankekar, author of Unsettling India: Affect, Temporality, Transnationality

“Jugaad Time is an important intervention into cartographies of postdigital media cultures. By drawing on the specificity of South Asian cultures, it enriches our understanding of the heterogeneity of these processes. The postcolonial study of media technologies is a vibrant and crucial field of inquiry; Amit S. Rai’s outstanding work is an essential contribution to global approaches to new media scholarship.” — Tiziana Terranova, author of Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age

The event form parts of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme Time Portals.

Octavia E Butler had a vision of time as circular, giving meaning to acts of courage and persistence. In the face of social and environmental injustice, setbacks are guaranteed, no gains are made or held without struggle, but societal woes will pass and our time will come and again. In this sense, history offers solace, inspiration, and perhaps even a prediction of what to prepare for.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

*Please not this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

Editors present: Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, Inte Gloerich

State Machines: Reflections and Actions at the Edge of Digital Citizenship, Finance, and Art

Today, we live in a world where every time we turn on our smartphones, we are inextricably tied by data, laws and flowing bytes to different countries. A world in which personal expressions are framed and mediated by digital platforms, and where new kinds of currencies, financial exchange and even labor bypass corporations and governments. Simultaneously, the same technologies increase governmental powers of surveillance, allow corporations to extract ever more complex working arrangements and do little to slow the construction of actual walls along actual borders. On the one hand, the agency of individuals and groups is starting to approach that of nation states; on the other, our mobility and hard-won rights are under threat. What tools do we need to understand this world, and how can art assist in envisioning and enacting other possible futures?

This publication investigates the new relationships between states, citizens and the stateless made possible by emerging technologies. It is the result of a two-year EU-funded collaboration between Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL), NeMe (CY), and a diverse range of artists, curators, theorists and audiences. State Machines insists on the need for new forms of expression and new artistic practices to address the most urgent questions of our time, and seeks to educate and empower the digital subjects of today to become active, engaged, and effective digital citizens of tomorrow.

James Bridle, Max Dovey, Marc Garrett, Valeria Graziano, Max Haiven, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Francis Hunger, Helen Kaplinsky, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak, Rhea Myers, Emily van der Nagel, Rachel O’Dwyer, Lídia Pereira, Rebecca L. Stein, Cassie Thornton, Paul Vanouse, Patricia de Vries, Krystian Woznicki.

Join editors Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, Inte Gloerich, contributors Max Dovey and Helen Kaplinsky, and respondent Ruth Catlow on Tue 23 Apr from 18.00-20.30 for short presentations with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park*

*Please note this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

ART AFTER MONEY, MONEY AFTER ART is a workshop with Max Haiven, author of Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

In a world turned into a casino is it any wonder that corporate gangsters increasingly run the show? What are the prospects for a democratization of the economy when new technologies appear to further enclose us in a financialized web where every aspect of life is transformed into a digitized asset to be leveraged? Ours seems to be an age when art seems helpless in the face of rising authoritarianism, or like the plaything of the worlds speculator-plutocrats, and age when “creativity” has become the buzzword for the violent reorganization of work and urban life towards an endless “now” of competition and austerity.

And yet… we are witnessing an effervescence of imaginative struggles to challenge, hack and reinvent “the economy.” Artists, technologists and activists are working together not only to refuse the hypercapitalist paradigm but reinvent the methods and measures of cooperation towards different futures. This workshop brings together many of these protagonists and their allies for a discussion on the occasion of the publication of Max Haiven’s new book Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

Haiven will kick off the conversation with a short presentation of key themes in the book as they impinge upon the question of working at the intersection of “art” and new technologies (including but not limited to blockchains) to create alternative economic paradigms. The central question is, to what extent can these efforts surpass the (important) desire to redistribute wealth in a world of growing inequalities and, additionally, aim for a much more profound and radical collective reimagining of who and what is valuable.

Austin Houldsworth

Dan Edlestyn

Brett Scott

Cassie Thornton

Kate Genevieve

Emily Rosamond

Jonathan Harris

Ruth Catlow and Martin Zeilinger will chair discussions and the event is sponsored by Anglia Ruskin University

Pluto Press are happy to offer a Furtherfield discount on the book. Add Art After Money to the cart and use the discount code ART15 to get the book at £15.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

The blockchain is widely heralded as the new internet – another dimension in an ever-faster, ever-more powerful interlocking of ideas, actions and values. Principally the blockchain is a ledger distributed across a large array of machines that enables digital ownership and exchange without a central administering body. Within the arts it has profound implications as both a means of organising and distributing material, and as a new subject and medium for artistic exploration.

This landmark publication brings together a diverse array of artists and researchers engaged with the blockchain, unpacking, critiquing and marking the arrival of it on the cultural landscape for a broad readership across the arts and humanities.

Contributors: César Escudero Andaluz, Jaya Klara Brekke, Theodoros Chiotis, Ami Clarke, Simon Denny, The Design Informatics Research Centre (Edinburgh), Max Dovey, Mat Dryhurst, Primavera De Filippi, Peter Gomes, Elias Haase, Juhee Hahm, Max Hampshire, Kimberley ter Heerdt, Holly Herndon, Helen Kaplinsky, Paul Kolling, Elli Kuru , Nikki Loef, Bjørn Magnhildøen, Rhea Myers, Martín Nadal, Rachel O Dwyer, Edward Picot, Paul Seidler, Hito Steyerl, Surfatial, Lina Theodorou, Pablo Velasco, Ben Vickers, Mark Waugh, Cecilia Wee, and Martin Zeilinger.

Read a review of the book by Regine Debatty for We Make Money Not Art

Read a review of the book by Jess Houlgrave for Medium

Date:NOW

Venue:HERE Links:http://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/artists-rethinking-the-blockchain?tk=208334da9b174c..

WE WANT your submissions to this landmark publication marking and augmenting the arrival of a new technology on the cultural landscape.

THE BLOCKCHAIN is widely heralded as the new internet – another dimension in the ever-faster ever-more-powerful interlocking of ideas, actions and values. [1]

It’s nothing more than a ledger distributed across a large array of machines. An apparatus that enables digital ownership and exchange without a central administering body. But from these simple premises, it has been credited with the potential to transform everything, from trade, to cultural production, to the way we’re governed.

Among other things, we are suspicious of cultural production being brought under the same regime as finance.

Even as we write, this “new dawn” for transactions is being re-imagined as the next sleep-cycle taking us deeper into the neoliberal dream of complete financialisation. In this dream, Finance and Technology quicken their demented mining of value tokens from phenomena, while the grammars of culture, family, nature, politics and spacetime itself evaporate into a flurry of question and exclamation marks in their wake.

“It’s going to change everything!” (The Guardian)

The permanence and irrevocable automation of blockchain systems wedded to the irrationality and sweep of techno-financial hybrids has led to forecasts ranging from ‘fully automated luxury communism’, to our ultimate cryptological enslavement to machines, or the collapse of time itself, as the feature of algorithms to make-happen overtakes the temporal concerns of flesh and earth.

Artists Re:thinking The Blockchain

This book is not a site for a ludic cynicism or uncritical valorisation, though it celebrates the energies of these excessive forms of thinking. We welcome the potentials for ever more nuanced democratic apparatus, and the decentralization of power from state-corporation cabals, while rejecting the notion that any single technology would automatically enact these ideological transformations. We seek also to register and amplify the leakages, weirdness and side-effects that this new technology inaugurates.

Imagined as a future-artefact of a time before the blockchain changed the world, and a protocol by which a community of thinkers can transform what that future might be, Artists Re:Thinking The Blockchain acts as a gathering and focusing of contemporary ideas surrounding this still largely mythical technology.

The book will include examples and discussions of current artistic projects making use of and illustrating the potentials of the blockchain, theorisation from some of the leading figures in the global blockchain conversation, and practical discussions which artists can use to guide their first steps towards this new technology.

We welcome submissions of

· book-based artworks which reflect on blockchain themes

· science fictions and theorisations, particularly in their hybrid form

· proposals for documentation of online and irl artworks

· poems, particularly based on the ‘new book’ and formal constraint txtblock [2]

The publication is a collaboration between Torque and Furtherfield, connecting Furtherfield’s Art Data Money project with Torque’s experimental publishing programme.

Alongside an illustrated print edition, the project includes a range of public-participation and debating sessions in towns and cities up and down the UK, and the first-ever book launch taking place on the blockchain itself.

DEADLINE FOR PROPOSALS 15th August

– up to 500-word abstract, description or sample of your proposed submission

– a short bio

– website link (optional)

mail to: mail@torquetorque.net

DEADLINE FOR FINAL SUBMISSIONS will be 1st October

torquetorque.net || furtherfield.org

https://www.facebook.com/torquebooks

#artblockbook

Contact: mail@torquetorque.net

Featured Image: Gerald Raunig, Dividuum, Semiotext (e)/ MIT Press

Gerald Raunig’s book on the concept and the genealogy of “dividuum” is a learned tour de force about what is supposed to be replacing the individual, if the latter is going to “break down” – as Raunig suggests. The dividuum is presented as a concept with roots in Epicurean and Platonic philosophy that has been most controversially disputed in medieval philosophy and achieves new relevance in our days, i.e. the era of machinic capitalism.

The word dividuum appears for the first time in a comedy by Plautus from the year 211 BC . “Dividuom facere” is Ancient Latin for making something divisible that has not been able to be divided before. This is at the core of dividuality that is presented here as a counter-concept to individuality.

Raunig introduces the notion of dividuality by presenting a section of the comedy “Rudens” by Plautus. The free citizen Daemones is faced with a problem: His slave Gripus pulls a treasure from the sea that belongs to the slave-holder Labrax and demands his share. Technically the treasure belongs to the slave-holder, and not to the slave. Yet, in terms of pragmatic reasoning there would have been no treasure if the slave hadn’t pulled it from the sea and declared it as found to his master. Daemones comes up with a solution that he calls “dividuom facere”. He assigns half of the money to Labrax, who is technically the owner, if he sets free Ampelisca, a female slave whom Gripus loves. The other half of the treasure is assigned to Gripus for buying himself out of slavery. This will allow Gripus to marry Ampelisca and it will also benefit the patriarch’s wealth. Raunig points out that Daemones transfers formerly indivisible rights and statuses – that of the finder and that of the owner – into a multiple assignment of findership and ownership.

We will later in the book see how Raunig sees this magic trick being reproduced in contemporary society, when we turn or are turned into producer/consumers, photographers/photographed, players/instruments, surveyors/surveyed under the guiding imperative of “free/ voluntary obedience [freiwilliger Gehorsam]”.

The reader need not be scared by text sections in Ancient Greek, Ancient Latin, Modern Latin or Middle High German, as Raunig provides with translations. The translator Aileen Derieg must be praised for having undertaken this difficult task once more for the English language version of the book. It can however be questioned whether issues of proper or improper translation of Greek terms into Latin in Cicero’s writings in the first century BC should be discussed in the context of this book. This seems to be a matter for an old philology publication, rather than for a Semiotext(e) issue.

It is, however, interesting to see how Raunig’s genealogy of the dividuum portraits scholastic quarrels as philosophic background for the development of the dividuum. With the trinity of God, Son of God and the Holy Spirit the Christian dogma faced a problem of explaining how a trinity and a simultaneous unity of God could be implemented in a plausible and consistent fashion. Attempts to speak of the three personae (masks) of God or to propose that father, son and spirit were just three modes (modalism) of the one god led to accusations of heresy. Gilbert de Poitiers’ “rationes” were methodological constructions that claimed at least two different approaches to reasoning: One in the realm of the godly and the other in the creaturely realm. Unity and plurality could in this way be detected in the former and the latter realm respectively without contradicting each other. Gilbert arrives at a point where he concludes that “diversity and conformity are not to be seen as mutually exclusive, but rather as mutually conditional.” Dissimilarity is a property of the individual that forms a whole in space and time. The dividual, however, is characterized by similarity, or in Gilbert de Poitiers’ words: co-formity. “Co-formity means that parts that share their form with others assemblage along the dividual line. Dividuality emerges as assemblage of co-formity to form-multiplicity. The dividual type of singularity runs through various single things according to their similar properties. … This co-formity, multi-formity constitutes the dividual parts as unum dividuum.”

In contemporary society the one that can be divided, unum dividuum, can be found in “samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’”. Developing his argument in the footsteps of Gilles Deleuze, Gerald Raunig critically analyses Quantified Self, Life-Logging, purchases from Amazon, film recommendations from Netflix, Big Data and Facebook. “Facebook needs the self-division of individual users just as intelligence agencies continue to retain individual identities. Big Data on the other hand, is less interested in individuals and just as little interested in a totalization of data, but all the more so in data sets that are freely floating and as detailed as possible, which it can individually traverse.” In the beginning “Google & Co. tailor search results individually (geographical position, language, individual search history, personal profile, etc.” The qualitative leap from individual data to dividual data happens when the ”massive transition to machinic recommendation [happens], which save the customer the trouble of engaging in a relatively undetermined search process.” With this new form of searching the target of my search request is generated by my search history and by an opaque layer of preformatted selection criteria. The formerly individual subject of the search process turns into a dividuum that is asking for data and providing data, that is replying to the subject’s own questions and becomes interrogator and responder in one. This is where Gilbert de Poitiers’ unum dividuum reappers in the disguise of contemporary techno-rationality.

Raunig succeeds in creating a bridge from ancient and medieval texts to contemporary technologies and application areas. He discusses Arjun Appadurai’s theory of the “predatory dividualism”, speculates about Lev Sergeyevich Termen’s dividual machine from the 1920s that created a player that is played by technology, and theorizes on “dividual law” as observed in Hugo Chávez’ presidency or the Ecuadorian “Constituyente” from 2007. The reviewer mentions these few selected fields of Raunig’s research to show that his book is not far from an attempt to explain the whole world seamlessly from 210 BC to now, and one can’t help feeling overwhelmed by the text.

For some readers Raunig’s manneristic style of writing might be over the top, when he calls the paragraphs of his book “ritornelli”, when he introduces a chapter in the middle of his arguments that just lists people whom he wants to thank, or when he poetically goes beyond comprehensiveness and engages with grammatical extravaganzas in sentences like this one: “[: Crossing right through space, through time, through becoming and past. Eternal queer return. An eighty-thousand or roughly 368-old being traversing multiple individuals.”

It is obvious that Gerald Raunig owes the authors of the Anti-Œdipe stylistic inspirations, theoretical background and a terminological basis, when he talks of the molecular revolutions, desiring machines, the dividuum, deterritorialization, machinic subservience and lines of flight. He manages to contextualise a concept that has historic weight and current relevance within a wide field of cultural phenomena, philosophical positions, technological innovation and political problems. A great book.

Dividuum

Machinic Capitalism and Molecular Revolution

By Gerald Raunig

Translated by Aileen Derieg

Semiotext(e) / MIT Press

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/dividuum

Megan Prelinger is an historian/archivist (originally from Oregon) who in 2004 co-founded a bibliophile’s utopia: the Prelinger Library. Tucked away in the SOMA district of San Francisco–and now highly regarded by researchers from around the world–the library has quietly become a California landmark. The myriads of materials contained there (books and ephemera “geospatially” arranged by Megan and her partner Rick) are made available to the public at least once a week for in-situ use (and one needn’t have academic credentials to enter).

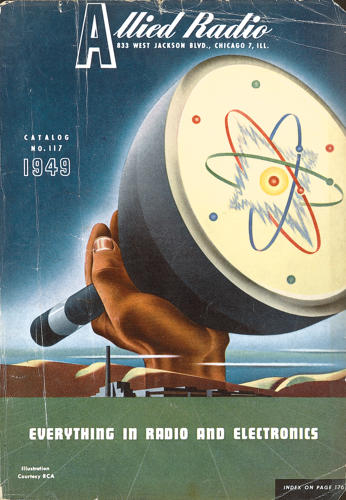

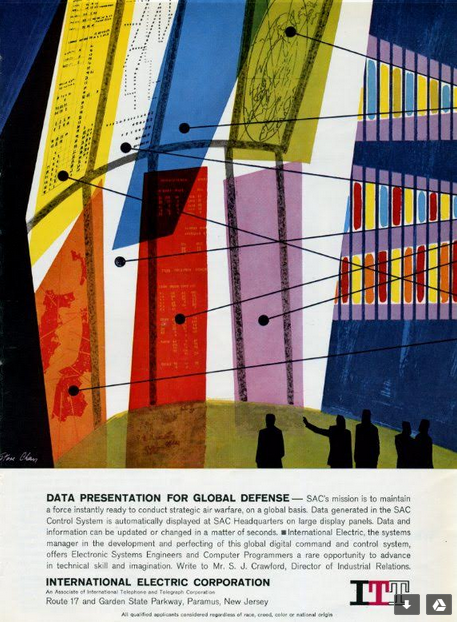

In addition to being a world-renowned sharer (and repairer!) of books though, Megan Prelinger has also authored several. Inside the Machine–her latest work–is a book that traces a visual history of all manner of electronics from roughly the interwar era to the early space age. But it derives its narrative, she says, from exactly and only one source: “the intersection of commerce and graphic art.” As with her previous book (which presents commercial artists’ depictions of early space travel and rocket tech), Inside The Machine is a story told largely through the illustrations that one finds scattered throughout archival tech ephemera–of the sort that line many a shelf at the Prelinger Library. Prelinger’s visually rich book deftly guides the reader through countless innovations that preceded today’s computers, all with an eye towards celebrating the power and reach of the human imagination.

[The following interview was conducted via email.]

Montgomery Cantsin: You say that the Prelinger Library and its community constitute the “rhythmic pulse” which sustains your work as a writer of nonfiction. I wonder if you can say a bit more about that, and how that maybe differs from the situation of many nonfiction writers–that of being ensconced in a bureaucratic university setting. Also, how much of the material in your newest book was discovered there on your own shelves in San Francisco?

Megan Prelinger: During the research and writing of Inside the Machine, between 2011 and 2014, I was simultaneously engaged in a number of projects. You ask about how my situation differs from that of an academic historian: The academic model did not fully “take” in my mind when I was younger. It was introduced to me as one option among many, and I elected take the option of being an independent and self-supporting contributor to the human knowledge project. Throughout the duration of the library project, and my life for that matter, I have therefore always engaged in a number of different types of work more or less simultaneously; types of work that fall in different places on the spectrum between “day job” and freelance artist or knowledge-producer.

My work-week during those Inside the Machine years, as before and since, was a cycle of different forms of research, engagement, and production. The common anchor point around which every week “turns” is the public day in the library that happens every Wednesday. On those public days I set aside my own work and face outward, engaging our library visitors and facilitating their work. The Wednesday community is intellectually sustaining, as hundreds of people every year who are engaged in a universe of different kinds of research-based projects stop by and spend time. Our library is a social library, with discussion being one aspect of the access model. As with visitors, the collaborative relationships I’ve had with our volunteers and artists-in-residence such as yourself have put that library environment at the center of my social, intellectual and creative life since we opened it

To answer the question about how much of the material of the book was discovered on our own shelves: The short answer is “most of it.” There are 184 images in Inside the Machine, I believe, and about 6 of them were sourced from other collections. It was the serendipitous discovery of these overlooked images that drove the research process that became both Another Science Fiction (2010), and Inside the Machine (2015).

MC: I know that your interest in space travel developed in part due to your love of Star Trek as a youth. Is your interest in electronics something that grew out of that? At what point in your career did you realize you were passionate enough about electronics to write a book? …Have you ever tinkered with the insides of machines?

MP: My love of space exploration has many antecedents and you’re correct that Star Trek: TOS is one of them. I was born in 1967 as Season Two was beginning, just in time to be exposed fairly uncritically to a regular stream of images on television that suggested that space exploration was an emerging and “normal” part of everyday life. I remember watching Apollo astronauts explore the Moon on TV, and as a small child formed the unexamined assumption that Star Trek and the Apollo program were in a fact-and-fiction relationship to one another that was analogous to the relationship between the Little House on the Prairie books (fictionalized history) and the real histories of European colonization of North America (fact).

At the same time my dad was away in Vietnam serving in the U.S. Army construction brigades, while my mom was in college studying to be an archaeologist. Mom exposed me to Native American history, and Dad exposed me to the challenges of reintegrating into society as a damaged war veteran. Dad then became an architect. Those two parental models oriented me to the ground-based world that I lived in. I grew up sharply aware of divisions in society because of these two models, and had a sense of myself as an actor in a distinctly ground-based society. I studied anthropology and became a writer in order to develop tools to understand and affect the course of society and history.

The area of my psychogeography that was shaped by visions of space exploration were filled in by science fiction, which formed a bridge between ground-based and space-based spheres. In my thirties I discovered the left-behind literature of the mid-century space industry, and discovered that those handy tools of cultural analysis and writing would enable me to make an original contribution to the cultural history of space exploration. I was gobsmacked by this discovery. It was an unexpected point of integration between realms of my intellectual life and psychogeography that had previously been united only in the lifelong practice of reading and appreciating science fiction.

Coincidentally, in the course of taking that degree in anthropology I was required in college to take a year of science as a distribution requirement. This was actually a wish come true, since part of me had wanted to be a math major from the beginning but I lacked the background to do college-level math. That year-long general science course for non-science majors was possibly my favorite class in college. One third of the years’ curriculum was devoted to exploring electronics, understanding how circuits worked, learning to read circuit diagrams, and ultimately building a simple working radio out of found materials.

When my research on the cultural history of space exploration led me to try to understand space electronics, that history was invaluable. My passion to understand electronics grew directly out of a desire to understand why space exploration technologies matured when they did, apart from geopolitics and funding streams. When I realized that space exploration in the 1950s was reliant on the simultaneous development of very large-scale computers (mainframes) and very small-scale computers (the miniaturization made possible by the transistor), I then felt an overwhelming impulse to share what I had learned with other people. Inside the Machine ended up with a space electronics chapter in the 8th position (out of 9 chapters), but space electronics was the starting point in my research and the rest of the book mushroomed out from it.

MC: The artists whose work is featured in your book (often anonymous at the time) were given the job of depicting a reality that exists, as you say, “behind reality.” You point to the inherent surrealism of such a task–can you expand on that? …You also note that in 1935, when the electric signals in the human brain were first detected, the study of the electricity, etc, was considered to be “a new assault on the mystery of life…”

MP: The study of the relationship between electricity and the human body is still pretty new. In fact, one reason that I wrote the book is that the future of the practical integration between electronics and the body could be immense enough that its recent history would be overshadowed. That history is already not commonly understood, even as people are increasingly symbiotic with their devices. I wrote the book to serve as a prehistory to counter any historical amnesia that may be induced by possible futures.

The scientific verification, in 1935, that life is reliant on a flow of electricity through the body, proved and extended an idea that Mary Shelley was working with in Frankenstein. Tracing the historical literature it’s interesting to watch the dialogue between electricity and the body migrate out of subcultures and into mainstream hard science over the past 200 years. I’m referring to subcultures like science fiction and also 19th-century experimental para-medical techniques, such as dosing people with electrical current to improve their health. That relationship was subjected to the changing standards of rigor around medical and scientific investigations over the 20th century. Today, work on electronic circuits that could have biomedical applications and that could actually be ingested and dissolved within the body is at the forefront of such research. Assuming that such circuits are developed and proven useful, I wouldn’t be surprised if they came to be a dominant biomedical technology.

When I say “behind reality” I’m referring most literally to the invisibility of the electron stream. While electricity can be made visible as illumination, the flow of electrons through electronic devices, on the other hand, is invisible. Hence, “Inside the Machine.” For a time the components that channeled the flow of electrons, such as vacuum tubes and switches, were visible on the inside of radio cabinets. Some 1930s radio cabinet designs deliberately revealed the circuit board in a gesture to demystify the flow of electrons and glamorize the components. That short window of visibility, however, quickly retreated in the face of ever more complex circuits and ever more “built” environments that housed them. The cultural signification around electronics came to be centered on the integral devices: radio, TV, and eventually computers and everything that flows from them. I felt that there was a cultural history of the components that combine to form electronic devices that needed to be told, and that it was the graphic artists and illustrators working for industry who had made that cultural history–a history that it became my job to expose and interpret for a contemporary audience.

At a more philosophical level, the flow of electrons multiplied our senses. By forming invisible channels through which sounds and images were carried and replicated, electronics created a hierarchy of sense perceptions that had immediate cultural and political significations. How else to characterize that phenomenon besides surreal? Coincidentally the fine art movement known as Surrealism emerged in the 1920s and radios very shortly thereafter, coming to market in the late 20s and exploding in popularity during the 1930s. Think of it this way: multiple electromechanical eyes, faces, ears, and mouths populating homes, offices, and streets, in the form of a proliferation of new gadgets. The world filling with sense receptor multipliers everywhere you look. A mountaintop may be media in the sense that it opens up a perspective impossible to gain any other (unassisted) way, but a climb up a mountain is a unique event offering a unique perspective. Electronic media, in contrast, are most profound in their most ordinary distinguishing feature, which is their simultaneous multiplicity.

MC: You bring up Lewis Mumford in the book, saying that he regarded the craftperson’s bench as a sort of “bridge between art and applied skill.” To what degree has Mumford’s work influenced your thinking?

MP: I discovered the work of Lewis Mumford back in high school and appreciated his broad-spectrum thinking on a range of ground-based systems, like cities and highways. (The first book of his that I read was The Highway and the City.) Back in high school it was a novelty to me that subjects like freeways and cities were written about as subjects in their own right. They hadn’t been previously represented in any spectrum of “subjects” that I had been exposed to. I also liked about Mumford that he incorporated ecological thinking into his philosophies of the built environment, and that his environmental politics predated, and therefore did not fit into, contemporary modes of approaching those subjects.

When it came to writing Inside the Machine, I drew on Mumford, who had once been a radio engineer, as a historian of technology (or “technics” in his parlance). His work to elaborate the relationship between fine art and applied art expressed by the craft bench was a needed historical context for discussing the relationship between craft and art.

MC: The constant need for an “enlargement of the military field of perception” has been hugely responsible for innovations in moving-image technology (I am quoting here from Paul Virilio’s book War and Cinema–which I found on your shelves). I wonder how things might have developed differently if such had not been the case? (In other words, if R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world instead of by Westinghouse, the Pentagon, etc.).

MP: Well… the need for an enlargement of the military field of perception may have been responsible for innovations in moving-image technology, but it must exceed that in the extent to which it influenced space technology! The original satellite programs around the world, both USSR and US, were funded and dedicated to that purpose.

To get back directly, though, to the question you pose: It’s one that opens the door to many interesting possible alternate realities. That’s one reason I became so deeply focused on the work that fine and applied artists did to paint the future of new technologies. If I can make a blanket characterization of those artists as a group: I don’t think they were motivated to pick up a pencil or brush by a desire to enlarge the military field of perception! Instead they were creating all kinds of hybrid visions of the future, including pastoral and surrealist elements that addressed the multiplication of the senses in very humane terms.

There are perhaps more examples of the possibilities you suggest than you might think. For example: the influence of Hugo Gernsback, for whom the science fiction Hugo award is named. Gernsback was an active futurist who promoted science fiction and speculative futures through the mass publication of a wide range of pulp fiction magazines. At the same time he was a serious radio and TV pioneer who founded a radio station, experimented with early television broadcasting, and published “straight” news and craft magazine for radio professionals and amateurs alike, such as Radio-Electronics and Science and Mechanics to name just two. His “straight” news and craft magazines typically had a futurist-oriented editorial edge; one that was uninterested in mapping problems or limits or real-world geopolitics onto the emergence of new technologies. I don’t doubt that Gernsback’s influence was a shaping force on the emergence of electronic technology in ways that may not be fully understood for years. I don’t mean to dwell on Gernsback — he’s been widely written about in histories and biographies and I have never felt the call to add much to his hagiography. But I’m mentioning him here to directly respond to your query of “What if (R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world)”. One more note: Tesla’s name was not attached to his invention in the way that Edison’s was, but he did invent AC (alternating current). Given that most people in the industrialized world use AC every day, I would argue that Tesla did guide the research and development of some of the essential infrastructure of everyday life.

MC: Toward the end of the book you wonder whether computers will someday be “grown” instead of built. Sounds cool! Brings to my mind certain left-field figures such as Bern Porter. …Porter chose to drop out of professional science (to pursue DIY “sci-art” and many other things) after having worked on the Manhattan Project. I thought of him while looking at your book, since he is also said to have helped develop the cathode ray tube. …I am curious, what you may have learned about humanity’s future by delving into all these inventions of the past?

MP: In crafting that conclusion I was putting together a few different pieces of real evidence and combining them in a hypothetical exercise. I didn’t think it was that crazy. Consider the following verifiable phenomena: The biomedical circuits that can be ingested and dissolved in the human body; the capacity of mycelia networks–underground networks of fungal bodies—to effectively redistribute nutrients between different plants in the soil; the published theory that life itself may have emerged from primordial clay (not “soup”); the wisdom of permaculture.

I’ve read widely about all these phenomena, and other related phenomena. When I try to visualize an answer to the problem of toxic chemicals and heavy metals bound up in electronic devices, it seems reasonable to me that a hundred years from now, or maybe even only twenty years from now, people will have figured out how to extract computational functions from some combination of these kinds of existing features of the natural world. Or will have developed some intelligent permaculture that can perform media functions at the same time as producing food.

Or, never mind organic phenomena, what if all the essential elements of sand, stone, glass, (plastic) and metal that form electronic machines could be formulated and constructed to smartly dematerialize when they were no longer needed? What if you could drop a laptop into special bin that would use magnets and clean biochemical processes to disassemble all those building blocks, and distill them into measured piles and vials of raw materials for new machines?

Maybe I’ve read too much science fiction… but I’d prefer to believe that I’ve just read too much history to feel that the possibilities for the future are in any way fixed or limited. In human history–in natural history too, for that matter–epochal shifts happen sometimes “overnight” (at least in geological or historical senses), usually from the emergence of a new phenomenon that results from combined antecedents that were hidden below the surface until abruptly transformed and brought to daylight. There’s no reason to think that the dirty century of the 20th/21st centuries couldn’t experience an abrupt paradigm shift in favor of a very different kind of model.

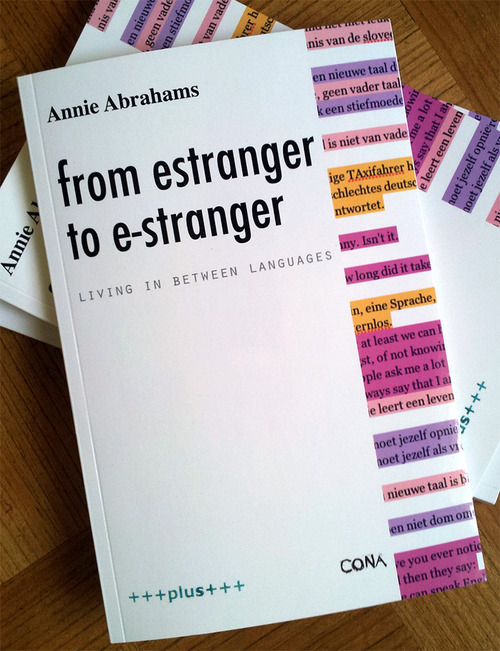

Gretta Louw reviews Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages, and finds that not only does it demonstrate a brilliant history in performance art, but, it is also a sharp and poetic critique about language and everyday culture.

Annie Abrahams is a widely acknowledged pioneer of the networked performance genre. Landmark telematic works like One the Puppet of the Other (2007), performed with Nicolas Frespech and screened live at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, or her online performance series Angry Women have solidified her position as one of the most innovative net performance artists, who looks not just at the technology itself but digs deeper to discover the ways in which it impacts human behaviour and communication. Even in the present moment, when online performativity is gaining considerable traction (consider the buzz around Amalia Ulman’s recent Instagram project, for example), Abrahams’ work feels rather unique. The strategy is one of contradiction; an intimacy or emotionality of concept and content, juxtaposed against – or, more accurately, mediated through – the technical, the digital, the screen and the network to which it is a portal. Her recent work, however, is shifting towards a more direct interpersonal and internal investigation that is to a great extent nevertheless formed by the forces of digitalisation and cultural globalisation.

(E)stranger is the title that Abrahams gave to her research project at CONA in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and which led to the subsequent exhibition, Mie Lahkoo Pomagate? (can you help me?) at Axioma. The project is an examination of the shaky, uncertain terrain of being a foreigner in a new land; the unknowingness and helplessness, when one doesn’t speak the language well or at all. Abrahams approaches this topic from an autobiographical perspective, relating this experiment – a residency about language and foreignness in Slovenia. A country with which she was not familiar and a language that she does not speak – regressing with her childhood and young adulthood experiences of suddenly being, linguistically speaking, a fish out of water. This experience took her back to when she went to high school and realised with a shock that, she spoke a dialect but not the standard Dutch of her classmates, and then this situation arose again later when she moved to France and had to learn French as a young adult.

There are emotional and psychological aspects here that are significant and poignant – and ‘extremely’ often overlooked. The way one speaks and articulates oneself is so often equated with intelligence and authority – and thus the foreigner, the newcomer, the language student, is immediately at a disadvantage in the social hierarchy and power distribution. Then, there are the emotional aspects and characteristics requisite for learning a language; one must be willing to make oneself vulnerable, to make mistakes. This is a drain on energy, strength, and confidence that is rarely if ever acknowledged in the current discourse around the EU, migration, asylum seekers, and – that dangerous word – assimilation. Abrahams lays her own experiences, struggles, and frustrations bare in a completely matter-of-fact way, prompting a re-thinking of these commonly held perceptions and exploring the ways that language pervade seemingly all aspects of thought, self, and relationships.

Of course this theme is all the more acute in a world that is increasingly dominated by if not the actual reality of a complete, coherent, and functioning network, then at least the illusion of one. In a world where, supposedly, we can all communicate with one another, there is increasing pressure to do so. Being connected, being ‘influential’ online, representing and presenting oneself online, branding, image – these are factors that are becoming virtues in and of themselves. Silicon Valley moguls like Mark Zuckerberg have spent the last five or six years carefully constructing a language in which online sharing, openness, and connectivity are aligned explicitly with morality. Just one of the many highly problematic issues that this rhetoric tries to disguise is the inherent imperialism of the entire mainstream web 2.0 movement.

Abrahams’ book from estranger to e-stranger: Living in between languages is the analogue pendant to the blog, e-stranger.tumblr.com, that she began working on as a way to gather and present her research, thoughts, and documentation from performances and experiments during her residency at CONA in April 2014 and beyond. Her musings on, for instance, the effect dubbing films and tv programs from English into the local language, or simply screening the English original – how this seems to impact the population’s general fluency in English – raise significant questions about the globalisation of culture. And the internet is arguably even more influential than tv and cinema were/are because of the way it pervades every aspect of contemporary life.

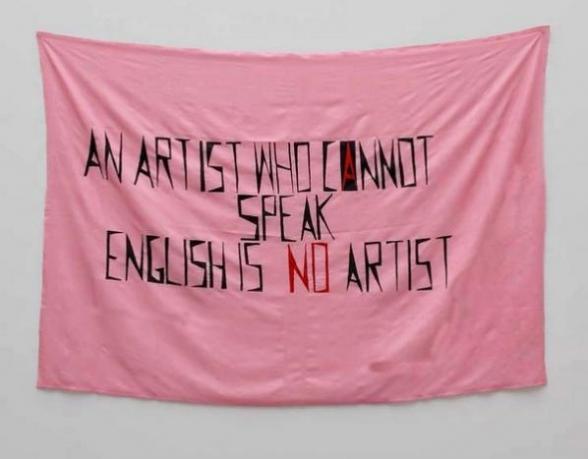

This leads one irrevocably to consider the digital colonialism of today’s internet; the overwhelming dominance of western, northern, mainstream, urban, and mostly english-speaking people/systems/cultural and power structures. [1] Abrahams highlights the way that this bleeds into other areas of work, society, and cultural production, for example, through her citation of Mladen Stilinovic’s piece An Artist Who Cannot Speak English is No Artist (1994). In a recent blog post, Abrahams further reveals the systematic inequity of linguistic imperialism and (usually English speakers’) monolingualism, when she delves into the language politics of the EU and its diplomacy and parliament [http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/post/139842799561/europe-language-politics-policy].

from estranger to e-stranger is an almost dadaist, associative, yet powerful interrogation of the accepted wisdoms, the supposed logic of language, and the power structures that it is routinely co-opted into enforcing. It is a consciously political act that Abrahams publishes her sometimes scattered text snippets – at turns associative or dissociative – in a wild mix of languages, still mostly English, but unfiltered, unedited, imperfect. A rebellion against the lengths to which non-native speakers are expected to go to disguise their linguistic idiosyncrasies (lest these imperfections be perceived as the result of imperfect thinking, logic, intelligence). And yet there is an ambivalence in Abrahams’ intimations about the internet that reflect the true complexity of this cultural and technological phenomena of digitalisation. Reading the book, one feels a keen criticism that is justifiably being levelled at the utopian web 2.0 rhetoric of democratisation, connection etc, but there are also moments of, perhaps, idealism, as when Abrahams asks “Is the internet my mother of tongues? a place where we are all nomads, where being a stranger to the other is the status quo.”

Abrahams’ project is timely, especially now that we are all (supposedly) living in an infinitely connected, post-cultural/post-national, online society, we are literally “living between languages”. The book is an excellent resource, because it is not a coherent, textual presentation of a thesis; of one way of thinking. It is, like the true face of the internet, a collection, a sample, of various thoughts, opinions, ideas, and examples from the past. One can read from estranger to e-stranger cover to cover, but even better is to dip in and out, and or to follow the links and different pages present, and be diverted to read another text that is mentioned, to return, to have an inspiration of one’s own and to follow that. But to keep coming back. There is more than enough food for thought here to sustain repeated readings.

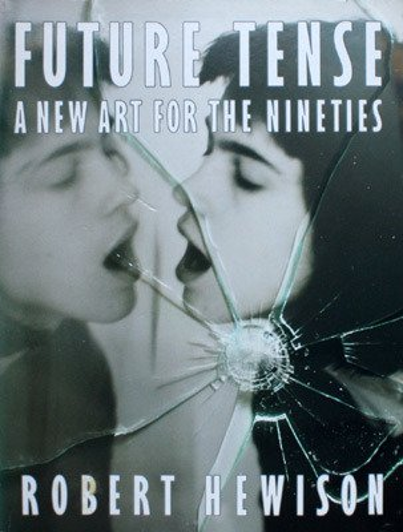

This article revisits Robert Hewison’s book, Future Tense: A New Art For The Nineties, [1] published in 1990. The book focused on contemporary attitudes to art, architecture and design that manifested in what had come to be called the postmodern era. Earlier avant-gardes of collectives and groups such as Dada, Situationism, Fluxus and the Lettrists had incorporated new technologies and challenged the material values embraced by museums and traditional hierarchies in modern art and capitalist society. Hewison set out to discover the ways in which artists of the 80s contributed to a “critical culture” for the 90s. [2]

In the 70s in the UK, art had a role to play in changing society, transforming relations to controlling production and critiquing the role of the establishment. Hewison’s mission was to observe contemporary culture happening in the late 80s in Britain with an emphasis on the future. Even though there had been a massive evolution in culture; within and across the fields of music, art and theory, it was also a new dawn for capitalism as it morphed into what we now know as neoliberalism. By revisiting Hewison’s book I hope to elucidate what the cultural shifts and differences in our art culture then and now are, and invite you the reader to reflect on what they mean to those of us engaging with and practicing across the fields of art, technology and social change today.

The way Hewison deals with postmodernism and its rapport with art and society is complex. He appears to regard much of the established art promoted in the late 80s, such as works by Jeff Koons, as banal marketing schemes, appealing to the interests of a privileged art-buying elite. He is more positive about grass roots communities re-appropriating and remixing art culture for others to claim on their terms. Michael Archer in his review of Present Tense in Marxism Today (1990) observed that not only was Hewison critical of modernism but also of postmodernism, which did little more than signal modernism’s ending. [3]

![[4] (Hewison 1990)](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/hewison1.jpg)

Lyotard argues that the grand narratives of 20th century modernism did not produce the benefits expected; rather, they have led to overt or covert systems of oppression. From this perspective the French Revolution and classic Marxism are seen only as forms of overarching and oppressive, ideology. Frederic Jameson offers another perspective on the ideas and social contexts around postmodernism. In his book Postmodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson says “It is safest to grasp the concept of postmodernism as an attempt to think the present historically in an age that has forgotten to think historically in the first place.” [5]

Future Tense’s cover image on the front of the book still feels contemporary. It shows a young woman about to kiss her mirror image while in front of a cracked glass, window. It alludes to a sense of culture – felt then as we still feel it now: as a disjointed picture of the world where modes of thinking and representation show us fragmentations, discontinuities and inter-textuality, and ‘bits-as-bits’ rather than unified objects. If the image were created now with a smashed up computer or mobile phone screen or an interface, its message would not be so different. We tend to beam our faces at our computer screens and then the screens beam right back at us, reflecting at us like data-mirrors, showing back not only a distorted image of ourselves but also a distorted multiverse.

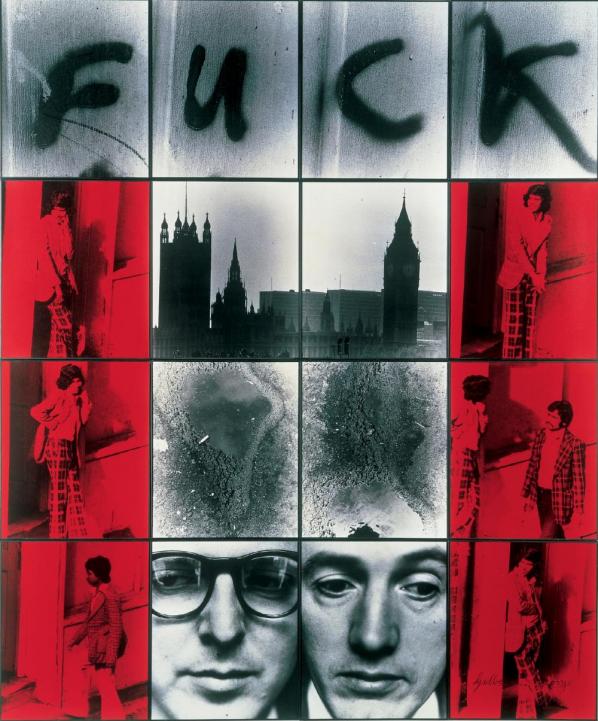

There has always been an irony at play with Gilbert & George. They usually expound a kind of punk aesthetic as an edgy chic; your lowest, basic, bigoted and unreconstructed inner ape giggles at their poo jokes. Yet while they subvert the idea of the ‘high’ of ‘high art’ by breaking life-style taboos they never bite the ‘high’ hand that feeds them. They know that shock is a dead cert currency just as the gutter press understands that sex and outrage sells, and that ethics and criticality get in the way of free market play. They sit well with the younger establishment in the arts, especially Damien Hirst and his peer YBAs, and similar Saatchi and Saatchi marketing investments.

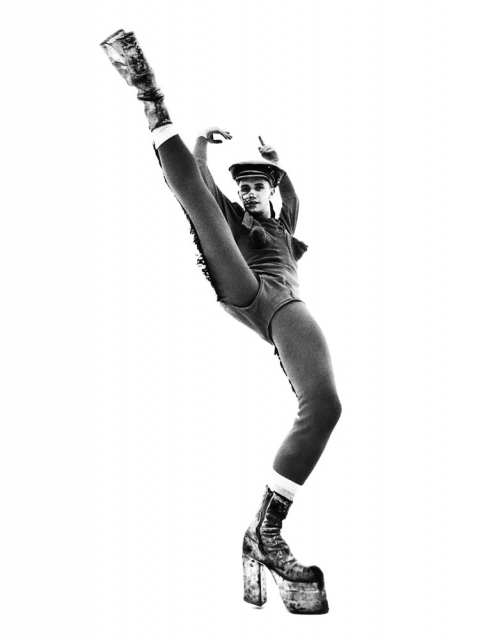

Hewison discusses Saatchi and Saatchi’s gallery space, and how the work presented in the space achieves an apparent purity, which detaches it from life, and that it has that autonomy within its own sphere which much twentieth-century art has sought to achieve. But in doing so it has separated itself from that other impulse, to use art as a means of revisualising, and so changing the world. [6] (Hewison 1990) This is still a big problem with art across the board even now. Most art agencies, orgs and galleries, are still separated from people’s everyday life experience. In contrast Michael Clark and his dance company was and still is a breath of fresh air. Even though he was classically trained, Clark tore “up the conventions of ballet, mixing sound and image in a rapid collage of creation, quotation and reference that plunders popular culture with calculated offence.” [7]

Cross cultural and interdisciplinary collaborations have been another marker of radical transformation in the postmodern era. Clark’s collaboration with the punk band The Fall in 1988 is a case in point where two different fields meet and create a brilliant outcome.

“I’ve always had a very strong relationship to music, to punk and pop – David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, especially The Fall. The Fall’s song “New Puritan” was kind of a clarion call to me, not just because its rhythm is so ramshackle. When you listen to it, you wonder, “How the fuck do the musicians stay together?” Apart from that, the song encouraged me to say, “Wow, I’ll do it just like Mark E. Smith!” You know, “New Puritan” was against the idea of a big company, and I didn’t want to be employed by anyone. I didn’t want to sign a contract. I wanted to make my own work. I wanted independence, my own company. Mark E. Smith was definitely an example for that.” [8] (Clark 2014)

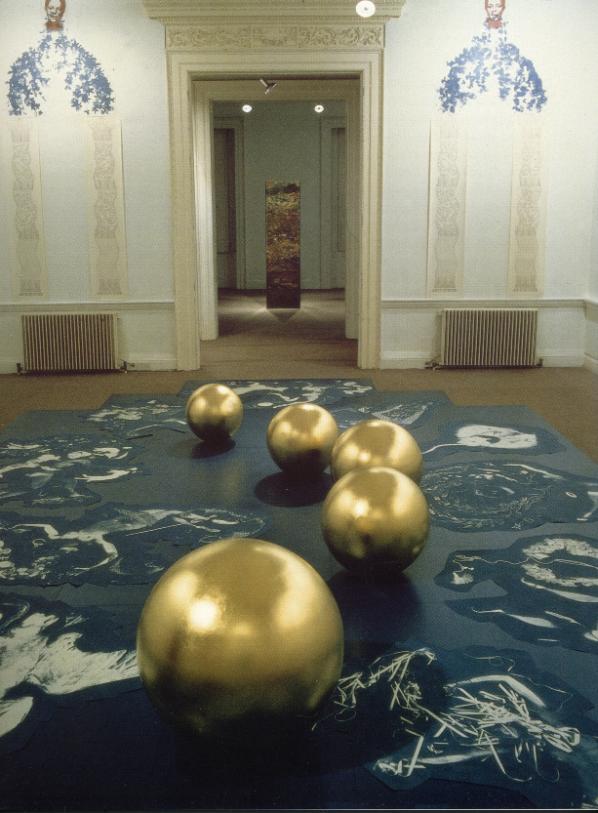

Many women artists during the 80s and 90s were using their bodies and identity as part of their art practice. Perhaps, one of the most treasured in the UK and greatly missed is Helen Chadwick who died on the 15th March 1996.

“Long before the current artistic obsession with the human body as a means for exploring identity, Chadwick had declared that “my apparatus is a body x [multiplied by] sensory systems with which to correlate experience”” [9] (Buck 1996)

Yet, her work resonates beyond her time period and still lives on through individuals inspired by her imaginative works to this day. Hewison dedicates five pages to Chadwick, and when discussing her installation Of Mutability, he says her work possessed a particular autonomy and, “Chadwick has found that the piece is most quickly appreciated by bisexuals who apprehend more easily the polymorphous nature desire.” [10] (Hewison 1990)

Hewison refers to the media baron Cardinal Borgia Gint in Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee, the baron in the film says “You wanna know my story, babe, it’s easy. This is the generation of who forgot how to lead their lives. They were so busy watching my endless movie. It’s power, Babe. Power. I don’t create it, I own it. I sucked and sucked and sucked. The Media became their only reality, and I owned the world of flickering shadows – BBC, TUC, ATV, ABC, ITV, CIA, CBA, NFT, MGM, C of E. You name it – I bought them all, and rearranged the alphabet.” [11]

Hewison talks about the destructive power of Rupert Murdoch and other media barons at the time. Even today the UK has been relentlessly plagued by the Murdoch empire, which a couple of years ago accidentally revealed its true colours forcing a decision to close the News of the World paper when it found itself at the centre of a phone-hacking scandal. Employees of the newspaper were accused of engaging in phone hacking, police bribery, and exercising improper influence in the pursuit of stories [12]. Particularly damaging was the discovery by investigators that not only were the phones of public figures hacked- celebrities, politicians and British Royal Family members- but also the phones of private individuals, already innocent victims of public tragedies such as the murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler and victims of the 7 July 2005 London bombings. The lives of us all are fair game as raw material for stories for the media markets.

Jubilee is one of those films that have so much in it and whenever I watch it again I always see something new. “The film originated in Jarman’s friendship with Jordan, the front woman for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s most outrageous designs for Sex and then Seditionaries – and a punk icon. Jubilee included several punk groups in this state-of-the-nation address – Adam and the Ants, the Slits, Wayne County – marking the start of a fertile relationship with the music industry.” [13]

Revisiting Future Tense reminds us how influential and necessary punk was, and still is in creating the conditions for emancipation and artistic freedom. While postmodernism is able to describe and explain the workings of the postindustrial media ecologies it doesn’t create artistic agency. We don’t need it to make change. It’s main agency still remains within an academic framework. In contrast punk expanded beyond and reached the middle classes, but also included working class culture and influenced new forms of independent, collaborative and artistic expression.

“The credo that Anyone Can Do It reached a mass of individuals and groups not content with their assigned cultural roles as disaffected consumers watching the world go by. Like the Situationists, Punk was not merely reflecting or reinterpreting the world it was also about transforming it at an everyday level” [14]

Introducing dualities tends to force us into observing things with combative eyes and not as various levels of artistic engagements and situated knowledges. Of course, the other part of the story is artists’ use of technology and how this has a lineage in its own right. But, Future Tense is still relevant and all the more poignant because looking back reminds us how much creative imagination has been hidden, forgotten and lost by art institutions, galleries and art magazines, as they rely on the same historical canons, generation after generation. The last real social and Cultural Revolution, artistic evolution or even renaissance, was with punk. Although since the Internet we can now include glimmers of hope with Net Art and Tactical Media, and strands of hacktivism, early pirate radio and TV, and BBS’s. It’s obvious that corporations and their markets have wedged in their own yes men (and women) as troops to counteract and prevent the occurrence of another explosion of emancipation.

Ask yourself how many people working in the media or in the arts: the funding sector, art agencies, art galleries, art mags, art organisations, are from working class backgrounds? Where do the possibilities exist for actual artistic emancipation? All around me I see opportunities closing down and people closing the doors behind them; as the conditions imposed by the neoliberal 1% hoover up all of the resources, through the invention of Austerity measures. In fact, there are only a few artists and art organisations daring to even mention that neoliberalism even exists, self-censoring them selves so that their funding or jobs are not suddenly compromised. By going along with this we participate in killing our imaginations and artistic freedoms for expression now and in the future, dumbing everything down across the board. Don’t just take my word for it. Hewison’s latest book about culture and political policy published in 2014 Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain describes the impact of New Labour, targets, and an instrumentalised meritocratic ideology in the time of Cool Britannia and the 2012 Olympics and offers an in-depth account of creative Britain losing its way.

“It’s not a pretty sight, and his findings of folly, incompetence and vanity will entertain and disturb readers in equal measure. They should also embarrass any politicians and arts administrators who retain a degree of self-awareness.” [15]

Artists are now expected to be ‘AWSOME’, malleable entities. There is a pressure to try and get ahead of everyone else by repackaging one’s artistic intentions, ideas and behaviours under the (it’s obvious surely) ironic term innovation. This is so artists can morph to participate in a false economy that only accepts art to conform within the demands of a consumer, dominated remit. Thankfully, there are still grounded artists and networks of practice that understand the value to a wider culture of keeping their critical faculties sharp and experimenting with other ways to create, distribute and appreciate culture in the network age.

To end this short journey, I will leave you with a note from the conclusion of Future Tense– “[…] within the gaps and cracks of the present culture there are possibilities for renewal. Join up the cracks, and a network forms; follow the lines, and a new map appears. It points beyond the post-Modern.” Good advice….

Featured image: By Instagram users lynellspencer and banditqueen555

I’ve been thinking about the idea of home a lot recently. I’ve been traveling over three continents for the last 6 months, living out of hostels, surfing friend’s couches, and even staying in local homes through Couchsurfing or personal connections. In terms of my home, I’ve grown comfortable with no privacy, sleeping in a room of strangers with only a tiny locked box for security. While I knew in my head the contemporary home is always shifting, I didn’t start considering the impact of that until my own housing situation became so erratic.

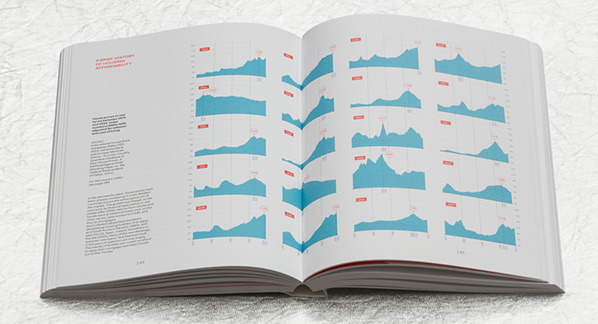

So I was excited to reflect further on the homes when the design research collaborative Space Caviar released a book of commissioned essays entitled, SQM: The Quantified Home. The essays examine how the romantic idea of the home is increasingly in tension with global market forces, zoning laws, new technologies, surveillance, war, and much more. The book was commissioned by Biennale Interieur and was part of Space Caviar’s program, “The Home Does Not Exist,” which premiered at the Biennale Interieur in Belgium in October of last year.

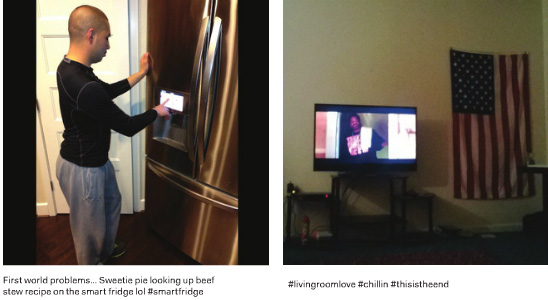

“Industry people today don’t actually want the home of the future. What they want is the homeowner of the future, as the kind of completely consumer-aware, Amazon-livestock guy… They don’t care what the shape of the house is, they just want the data flows in and out.” – Bruce Sterling, (pg. 236)

In his essay, Bruce Sterling asks us how the architecture and architects of the home will be disrupted – like the music and publishing industries were disrupted – for data optimization? As we’ve done for social media, we’re opening up our homes to private companies for the sake of security and ease. We’re putting security cameras in our children’s bedrooms and connecting our home to the cloud with devices such as Amazon Echo. How will the home as networked site look when created to produce as much advertising data as possible? How can a home look more like an Amazon warehouse?

In the networked home of the future, will we enter a Facebook-like power relationship, willingly rendering all our most private moments visible to marketers for a tax break or a free networked fridge? It sadly doesn’t sound too unlikely to me. SQM: The Quantified Home sets up a history and context to considering the realities of this kind of future home, making the clear complex data and politics already intersecting within our home.

Much of this opening up of the home is economically focused. Given the financial collapse of 2008 and subsequent austerity measures around the world, of which all but the mega-wealthy are still reeling from, we’ve been forced to use our homes as economic tools of investment as much as private spaces for family and loved ones. An investment which fewer and fewer people can afford to make. If architecture, homes, and even cities follow the trend of social media’s economic disparity – exchanging some free services for huge swaths of powerful and valuable data – it’s only going to get worse.

Selling acceptable looking cheap furniture that can barely survive its own assembly, Ikea is a perfect response to a generation that cannot afford a home. As career security grows more precarious, we’re increasingly moving cities and jobs, with Airbnb as a life raft for homeowners who can’t afford rent, and renters who can’t afford a home. The romantic ideas of “home” are collapsing all around us. As Alexandra Lange, author of Writing about Architecture: Mastering the Language of Buildings and Cities, notes, our Pinterests are filled with items we will never buy for homes we can no longer afford.

In, “The Commodification of Everything,” Dan Hill, the executive director of Futures at the UK’s Future Cities Catapult, looks at Marc Andreessen’s notion that, “software is eating the world,” and applies it to Airbnb and resident-led emergent urban interventions in Finland. While some celebrate often left-of-legal urban interventions, many of the same group cries foul when corporations like Airbnb do the same.

Hill writes, “It took Hilton a century to construct all of their hotels, brick by brick; Airbnb came along, armed only with software, and in six years created more without laying a brick.” (pg. 219) Hill asks us to further investigate how to use software in a civic way, protecting and enabling local culture and economies for the benefit of everyone. Hill writes that software “is eating the world, and it is only just booting up. Our response to that, as citizens and cities, will determine whether it does so for public good or for private gain.” (pg. 223)

So while the home is becoming a more fluid space, this predominately suits businesses or people like me because I have the freedom and privilege to move easily and earn a living wherever I have internet. Making housing more responsive to individual needs is nice advertising, but ignores larger housing markets and market forces all of us are subjected to.

Now, after reading this book and 6 months of travel with at least 6 more months to go, my idea of the home has shifted to be understood mostly in relation to family and friends. Moving through many different architecture styles, cultures, customs, and living situations have made me care less about the physical space of the home. However, this means that as the contemporary home becomes a site of surveillance, responsive, and transparentin relation to corporations and often governmental organizations, the contemporary home will place these networked spheres between us and those we most cherish.

Our most intimate settings – be it a home or an Airbnb room – now have corporations sitting right next to us. Just as we know you shouldn’t share anything you don’t want everyone to know on Facebook, in the future, we now know not to talk in front of your smart TV. The home may be the final site of privacy in modern cities yet many are actively sacrificing that privacy for a sense of security or for cool new products whose terms and conditions we never fully grasped.

Conversely, instead of placing ads between a couple cuddling on their networked bed of the future, the networked home is equally likely to put our entire social network into the bed with us in hopes of more clicks. We already see how social networks can favor clicks over meaningful connection. Joanne McNeil’s essay. “Happy Birthday,” continues a progression we’re already seeing to an always-on extreme where our birthdays are reduced to spam-like events where everyone we ever met and every object we encounter spews “Happy Birthday” ad nauseam.

This is of course a product of the advertising model of which most everything online is reliant on. Why would that change when the internet moves into your home? Indeed we already ask for this as 80% of 18 to 44 year olds check our phones first thing upon awakening. Now just turn your bed into the phone.

While networks moving into our home is cause for alarm, what was most startling to me about SQM: The Quantified Home, was the extent to which the home is already a site of many networked relationships between the city, few of which we control or are meaningfully transparent to the average homeowner. In “Postcode Demographics” Joseph Grima and Jonathan Nicholls discuss Acorn, an early program quantifying housing markets in the England. Using 60 metrics of classifications, Nicholls helped quantify neighborhoods for real-estate developers, homeowners, taxation, and more. The introduction of postal codes further quantified neighborhoods in a way likely many find helpful yet can lead to a kind of data lock-in. As these methods of quantification grow more complex, and the ramifications larger, the possibility of residents transcending their zip codes grows dimmer. We see this problem with funding of public schools in the states.

While we continue to connect to our homes and to each other in new ways, if those connections continue to benefit the Googles of the world the most, we’re in for trouble. Turning your home transparent to them and forgetting the place of the home within larger societal and civic concerns is dangerously shortsighted and will only benefit the big businesses. As Hill writes, whether these changes are to be net positive depends, “on how much we care about the idea of the city as a public good, how adept we are at absorbing and redirecting disruptive forces for civic returns.” (pg. 223)

Featured image: Stern, Body Language

Interactive Art and Embodiment: The Implicit Body As Performance by Nathaniel Stern. ISBN 978-1-78024-009-1 (printed publication), Gylphi Limited, Canterbury, UK, 2013. 291 pp., 41 Colour Stills.

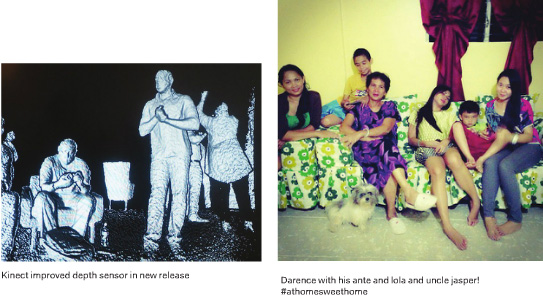

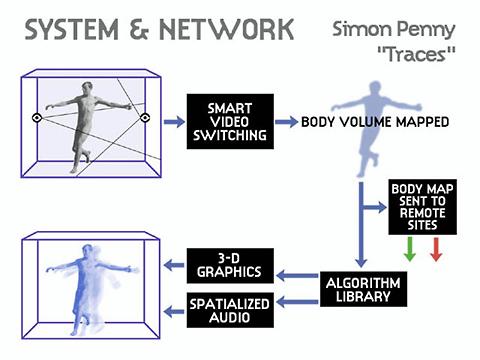

Earlier this year, I had the good fortune to sit in on a talk given by Simon Penny on May 6th 2014 at the University of Exeter. Penny, not unlike Nathaniel Stern, is best known for his praxis, writing and teaching on interactive (and robotic) installations focusing on issues of embodiment, relationality and materiality. So as unorthodox as its inclusion is to start off a review, Penny’s reflections are pertinent here (in this case, Penny’s famous installations Fugitive (1997) and Traces (1999) [1].

The purpose of Fugitive and Traces (if you can say they had one) sought to ‘embody’ virtual reality through multi-camera infra-red sensors, visual models and real-time movements. At that time, Penny’s unique theoretical take was to distance human-computer interaction away from “a system of abstracted and conventionalised signals” to where the user would “communicate kinesthetically”: instead of investigating the non-human or “inhuman” formal qualities of its medium, or some vague VR future that leaves the body behind, the system itself would “come closer to the native sensibilities of the human.” (Penny) [2]

In his Exeter talk, Penny momentarily reflected on a weird and altogether disturbing seventeen year feedback loop. The loop in question relates to how, in 2014, Penny’s early avant-garde ideas and theoretical ambitions have largely been desecrated by their replication in big business. With regard to Traces, Penny cited Microsoft’s Kinect as being the most salient example of this desecration: Kinect’s technology – marketed for the Xbox console brand – carries within its insidious techniques the ability to also “communicate kine[c]thetically”, but do so within pre-packaged, patented, IP-driven, focus-grouped-out-of-existence, commercial vacuities of gamer experience.

As an early practitioner and developer of these technologies, Penny was somewhat visibly infuriated with this, and understandably so. For him, it unintentionally reduced his aesthetic experimentation, philosophical insight, technological futurity and theoretical complexity into consumer speculation for the technology market, commandeering the tech but without the value. It transposed the artistic technological avant-garde necessity of Traces into a flaccid ‘tech-demo’ demonstration of novelty limb flailing and high-end visuals devoid of anything. It was, Penny lamented, “a very weird situation” to be in. Part of that weirdness has to do with the fact that Penny hadn’t done anything especially wrong, because there wasn’t any tangible aesthetic qualities that separated his pioneering work from Microsoft’s effort. Neither had Penny’s work brought financial success with its value intact (because its value wasn’t patentable). Instead technological development had overwritten the aesthetic value of Traces, trading technological obsolescence with aesthetic obsolescence.

Penny’s retroactive predicament is not unique in the history of digital art: for all the visionary seeds of potential in Roy Ascott’s legendary networking project, Terminal Art (1980) we now recognise how those salient characteristics have somehow ended up as Skype or Google Hangouts. Still in the 80s, one might evoke Eduardo Kac’s early videotext works (1985-1986) where visual animated poems were broadcast on the online service exchange platform Minitel (“Médium interactif par numérisation d’information téléphonique” or “Interactive medium by digitalizing telephone information” in its French iteration): a proprietary precursor to the World Wide Web [3]. The retroactive weirdness accompanying these developments is something I’ll come back to: suffice to say that what counts is the direction (and sometimes hostile return) of infrastructure, not just as the background collection of assemblages artists rely on to experiment with at any historical moment, but the shifting ecological foundations to which technology emerges, affords, and now overwrites such practices. No-one likes to play devil’s advocate and yet one must ask the question specific to Stern’s text: what, or maybe where, is the tangible point at which ‘art’ becomes historically valued in these works, if that latent aesthetic potential becomes just another market for a series of Silicon Valley, or startup conglomerates?

——–

Nathaniel Stern’s Interactive Art and Embodiment establishes two first events: not only Stern’s debut publication but also the first of a new series from Gylphi entitled “Arts Future Book” edited by Charlotte Frost, which began in 2013. All quotations are from this text unless otherwise stated.

Stern’s vision in brief: in order to rescue what is philosophically significant about interactive art, he justifies its worth through the primary acknowledgement of embodiment, relational situation, performance and sensation. In return, the usual dominant definitions of interactive art which focus on technological objects, or immaterial cultural representations thereof are secondary to the materiality of bodily movement. Comprehending digital interactive art purely as ‘art + technology’ is a secondary move and a “flawed priority” (6), which is instead underscored by a much deeper engagement, or framing, for how one becomes embodied in the work, as work. “I pose that we forget technology and remember the body” (6) Stern retorts, which is a “situational framework for the experience and practice of being and becoming.” (7). The concepts that are needed to disclose these insights are also identified as emergent.

“Sensible concepts are not only emerging, but emerging emergences: continuously constructed and constituted, re-constructed and re-constituted, through relationships with each other, the body, materiality, and more.” (205)

Interactive Art and Embodiment then, is the critical framework that engages, enriches and captivates the viewer with Stern’s vision, delineating the importance of digital interactive art together with its constitutive philosophy.